top Japanese photobooks of 2012

Posted: 28/12/2012 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists, Arimoto Shinya, Dodo Shunji, Hashimoto Katsuhiko, Hatsuzawa Ari, Ikazaki Shinobu, Kimura Hajime, Ogawa Takayuki, photobooks from Japan, Suda Issei, Tatsumi Naoya, Ōtsuka Megumi 6 CommentsInability to produce a list of the year’s best (from anywhere) doesn’t stop me from producing a list of the year’s best from Japan. For 2011 this was difficult, but this time around there’s a lot more good stuff (or I searched for it more energetically). And two dismissive messages I received a couple of weeks ago (“Top 10 lists, ugh!” and “the whole ‘best of’ thing leaves me a bit nauseous”) meant I just had to make a list. Even if you’re sufficiently insane to trust my judgment, the list can’t be authoritative: I haven’t yet got around to looking at Hamaura Shū’s Sorane and Watanabe Satoru’s Da.gasita. (Among what I didn’t bother to look at, there’s perhaps half of the product of the Araki and Moriyama industries — even putting aside the monumental contribution from Aperture — and of course a pile of books whose covers either exuded mere prettiness or just looked too boringly trendy.)

Big omissions:

- Arita Taiji’s First born. I remember skipping those pages of Camera Mainichi devoted to the series decades ago, and now that a book is at last available it still doesn’t click. But plenty of people whose opinions I value do appreciate it, so take a look.

- What’s arguably the year’s most outstanding Japanese photobook: I exclude Obara Kazuma’s book Reset: Beyond Fukushima merely because it happens not to be Japanese. (Though perhaps it’s not Japanese by necessity. Would any Japanese publisher have had the guts and energy to produce it?)

The order of what follows is merely alphabetical by photographer. I give Worldcat and CiNii links where I could find them; if I don’t give an ISBN then there isn’t one. I also give tips on where to buy. (I know the people who run Japan Exposures, but not well. I have no relation whatever to Bookofdays or Flotsam.) Where there’s no particular tip, you could try this service.

Arimoto Shinya, Ariphoto selection vol. 3 (Tokyo: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). 有元伸也, 『Ariphoto selection vol. 3』(東京: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). CiNii. The third fascicle (“volume” is rather a misnomer) of what I’d presumed was going to be a Shinjuku anthology but turns out not to be. Arimoto Shinya and his Rolleiflex returned to Tibet in 2009 (a decade after his Tibet book was published), and here’s the result. It’s 36.5×29.5 cm, containing just 16 B/W photographs, the majority of which are portraits. Like the two previous fascicles, it’s as slim and inexpensive as a zine but as well printed as a real photobook. You could buy two copies, cut them up and frame the pages for your personal Arimoto exhibition.

Arimoto Shinya, Ariphoto selection vol. 3 (Tokyo: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). 有元伸也, 『Ariphoto selection vol. 3』(東京: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). CiNii. The third fascicle (“volume” is rather a misnomer) of what I’d presumed was going to be a Shinjuku anthology but turns out not to be. Arimoto Shinya and his Rolleiflex returned to Tibet in 2009 (a decade after his Tibet book was published), and here’s the result. It’s 36.5×29.5 cm, containing just 16 B/W photographs, the majority of which are portraits. Like the two previous fascicles, it’s as slim and inexpensive as a zine but as well printed as a real photobook. You could buy two copies, cut them up and frame the pages for your personal Arimoto exhibition.

Available directly from the photographer (as is vol. 2).

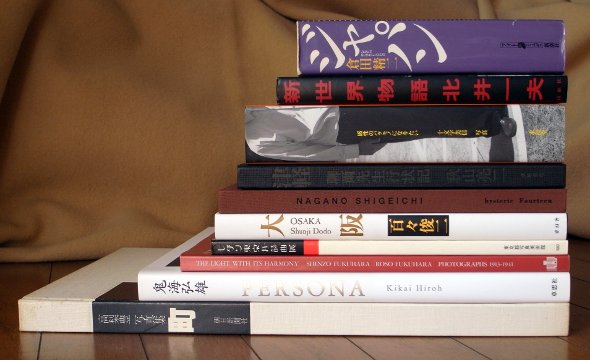

Dodo Shunji, Horizon far and away 1968–1977 (Tokyo: Akaaka-sha). 百々俊二, 『遙かなる地平 1968–1977』(東京: 赤々舎). ISBN 978-4-903545-87-5. CiNii, Worldcat. (This photo shows (A) the book as normally sold new in Japan: a translucent yellow cover goes over an obi which goes over (B) a very different cover; and (B) is how the book is sometimes advertised and perhaps also sold. Don’t worry; it’s the same book.)

Dodo Shunji, Horizon far and away 1968–1977 (Tokyo: Akaaka-sha). 百々俊二, 『遙かなる地平 1968–1977』(東京: 赤々舎). ISBN 978-4-903545-87-5. CiNii, Worldcat. (This photo shows (A) the book as normally sold new in Japan: a translucent yellow cover goes over an obi which goes over (B) a very different cover; and (B) is how the book is sometimes advertised and perhaps also sold. Don’t worry; it’s the same book.)

The photos in Dodo Shunji’s earliest photobook (1986) are lively but copies of this are elusive; the photos in his second (1995) are never less than workmanlike but for me the spark had gone and wouldn’t return until Osaka (2010). Yet in magazines and so on there have been glimpses of early, energetic work. At last here it is, anthologized in well over four hundred pages. It’s in twenty-six lettered sections, A to Z: we get student riots, down-at-heel quarters of Osaka, Dodo’s fiancée-then-wife, the infant Dodo Arata, protests close to US military bases, Americans close to these bases, short trips to London, Pusan, Hokkaidō, and more. It ends with the newborn Dodo Takeshi.

The subject matter and mood put this together with what Araki (minus repetition and obsessions), Tōmatsu and Kitai were doing at about the same time. A lot of photos are included on the strength of their atmosphere. Nobody would want to plod from start to end of this collection of three-hundred-plus photos — you’d take it in (diverse) instalments. It’s a book full of energy, and a delight.

All the photos are in B/W; but a variety of papers are used, the particular paper chosen to match the particular story. Each section is titled in Japanese and English. An interview that runs to almost twenty pages and in which Dodo comments on each lettered section is in Japanese only; but a postscript, potted bio and so on are in English too. It’s on the expensive side for a photobook of 19×26 cm format, but then it has a lot of pages.

The book is here at its publisher, and here at Sōkyūsha; if you’re outside Japan, it’s more simply available from Japan Exposures or from Bookofdays.

Hashimoto Katsuhiko. The other scenery. (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 橋本勝彦, 『もうひとつの風景』(東京: 蒼穹舍). (The English title only appears inconspicuously within the colophon; the reading of the Japanese title is Mō hitotsu no fūkei.) CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Hashimoto Katsuhiko. The other scenery. (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 橋本勝彦, 『もうひとつの風景』(東京: 蒼穹舍). (The English title only appears inconspicuously within the colophon; the reading of the Japanese title is Mō hitotsu no fūkei.) CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Another of (seemingly) dozens of elegantly packaged hardbacks from this publisher. The photographer finances the enterprise; and although there are editorial standards, a lot of these books are honourable and pleasant but no more. This one is squarely in the genre of views of untended corners of lived-in Japan, without people present. Perhaps the genre’s best-known exponent (for Tokyo) is Kikai Hiroh, but other good books include Fujita Mitsuru’s Zaisyo (the built-up countryside). (Such photos are also used for filler around photos with people in them.) Do we need yet more examples of the genre? No we don’t, but then we don’t need a lot of other photobooks either. And Hashimoto Katsuhiko has a good eye. What’s shown here is for the most part a crumbling, rusty, even grimy provincial Japan, but there’s always detail for pleasurable examination.

There are 52 B/W photographs, printed rather cheaply. (To my completely inexpert eye, the printed photos look like an educational demo of the results of the first stage of duotone printing.) I’m no fan of matching printing process to content and think the book would be more successful in tritone (of course economically impossible), but the lack of reproduction finesse does seem to add its own minor fascination.

In the back a list understandable even for Japanese and English monoglots says roughly where and when each photo was taken. And Hashimoto provides an afterword in the two languages. As for himself, we learn that he was born in Tokyo in 1942 and that he’s in a photo group named “Myaku”. Here’s a completely unrelated award-winning photo by him. For six days in October he had a small show at Nikon Salon bis (see the sole B/W photo here); I wish I’d known of it at the time, because I would have gone to see it. And this is all I know.

This is a small, unpretentious, modestly priced, and satisfying book.

Here’s the announcement from Sōkyūsha.

Hatsuzawa Ari, Rinjin. 38-do-sen no kita (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten). 初沢亜利, 『隣人。38度線の北』(東京: 徳間書店). ISBN 978-4-19-863524-4. Some of the material on the copyright page is in English but elsewhere the book is only in Japanese. The title means “Neighbours: North of the 38th parallel”.

Hatsuzawa Ari, Rinjin. 38-do-sen no kita (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten). 初沢亜利, 『隣人。38度線の北』(東京: 徳間書店). ISBN 978-4-19-863524-4. Some of the material on the copyright page is in English but elsewhere the book is only in Japanese. The title means “Neighbours: North of the 38th parallel”.

After his True feelings, a second photobook in one year by Hatsuzawa Ari, this time on North Korea, where he made four short trips from 2010. The book runs to 167 pages, of which pp. 5–78 are devoted to 平城 (Pyongyang) and pp. 79–153 to 新義州 (Sinŭiju), 咸興 (Hamhŭng), 元山 (Wŏnsan), 南浦 (Namp’o), 浮田 [?] and 金剛山 (Kŭmgangsan). Even in Japanese, there are no captions and there’s no other indication of whether the scene you’re looking at is (say) Hamhŭng or Wŏnsan.

Well, no matter. The neighbours north of the 38th parallel don’t always look so unlike the Japanese. They ride bikes, they frolic in the sea, they picnic, they wear Hello Kitty clothing — they tend to look rather normal as they go about their daily life. It’s a world away from the North Korea of Charlie Crane. (If the people stiffened or mugged for the camera, Hatsuzawa eliminated those photos.) This is no tourist memento but it’s sympathetic, and like True feelings it shows Hatsuzawa’s mastery of colour.

If Hatsuzawa’s book interests you, look also for Watanabe Hiroshi’s Ideology in paradise (パラダイス・イデオロギー): Watanabe’s cooler approach complements Hatsuzawa’s warmer one.

Ikazaki Shinobu, Inaya tol (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 伊ヶ崎忍, 『Inaya tol』(東京: 蒼穹舍). CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Ikazaki Shinobu, Inaya tol (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 伊ヶ崎忍, 『Inaya tol』(東京: 蒼穹舍). CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Ikazaki writes of Inaya Tol:

There is a very small and uncharted area on the Vishnumarti River, which flows behind the old royal place in Katmandu. This place is known as “Inaya [Tol]”. There are many Khasai buffalo slaughterhouses built tightly-packed in this area. Khasai people belong to the Newar, who were the earliest inhabitants [of] Nepal, and [are discriminated against].

He adds that the meat-eating Khasai are the lowest caste of the lowest class (or vice versa, or similar), but that their economic status has improved in recent years, so that members of (traditionally) higher castes/classes can now be seen employed by them.

There are no captions, in any language. There’s an afterword and a potted CV in Japanese and English, and that’s it.

The book alternates sections in B/W (printed well) and sections in colour (printed so-so). The former are more successful, but there are some fine photos in colour too.

There are dead animals (and bits thereof), live ones, and most disturbingly a live animal next to the head of a dead one, and a very small child wandering among the carnage. There’s a small amount of mild mugging by the workers, but not while they’re working: these aren’t psychopaths; they’re instead regular people doing a repellent job in a matter-of-fact way, which Ikazaki seems to view neutrally.

Here’s the announcement of the book at Sōkyūsha. It’s available from Japan Exposures.

Kimura Hajime, Kodama (Tokyo: Mado-sha). 木村肇, 『谺』(東京: 窓社). ISBN 978-4-89625-115-9. CiNii, Worldcat.

Kimura Hajime, Kodama (Tokyo: Mado-sha). 木村肇, 『谺』(東京: 窓社). ISBN 978-4-89625-115-9. CiNii, Worldcat.

I picked this off a shelf because I noticed “Kimura” and sleepily mistook the book for some new collection by Kimura Ihee (whose deservedly famous colour photography of Paris has outside Japan quite eclipsed his B/W work). Wrong: this book is by a different and much younger Kimura. But it’s no disappointment. (Indeed, new collections of work by Kimura Ihee tend to be either humdrum or very expensive.)

Kodama here means “echo”, with mountain/valley connotations. (Elsewhere it’s also a surname whose meaning, if any, is unrelated.) Kimura Hajime photographed on the snowy west coast of Japan, following hunters. Clothing aside, the scenes could be from the 1960s or even earlier — emphasized by the strong compositions and high contrast, as if this were newly discovered work by Kojima Ichirō.

A major annoyance: a significant number of the photos (including the excellent one reproduced on the front cover) are split across facing pages; and because the book is (unlike, say, Concresco) bound conventionally, the viewer’s brain then has to relate two separated chunks of a photo while ignoring a substantial median chunk. (Calling all photobook designers/publishers: Don’t do this.) But enough other photos can be enjoyed uninterruptedly. And there are captions in both Japanese and English for each.

Here’s Kimura’s page about his book.

Ogawa Takayuki, New York is (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 小川隆之, 『New York is』(東京: Akio Nagasawa). Worldcat, CiNii.

Ogawa Takayuki, New York is (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 小川隆之, 『New York is』(東京: Akio Nagasawa). Worldcat, CiNii.

Ogawa Takayuki (1936–2008) was in New York for less than eleven months, from April 1968. Though he has long been known in Japan (p. 81 of The Observer’s Book of Japanese Photographers is devoted to him), and though CiNii reveals that he (or a namesake) provided the photographs for a 1980 book titled American antique dolls (アメリカ人形 アンティークドール), this seems to be his first real photobook. It’s quite a production, with texts by Nathan Lyons, Anne Wilkes Tucker and (very briefly) Robert Frank.

Look inside and you soon see that while it merits these texts it doesn’t need them. The book is compact (21×22 cm) and not cheap; but it’s also not exorbitantly priced and it has 120 or so excellently printed photos, which are in a sort of Ishimoto or Frank mode and (harder to pull off) are in the same league. There are no duds. This is good stuff indeed.

Here’s the book at its publisher’s website. There’s a helpful write-up on its sales page at Japan Exposures.

Ōtsuka Megumi, Tokyo (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 大塚めぐみ, 『Tokyo』(東京: 蒼穹舍).

Ōtsuka Megumi, Tokyo (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 大塚めぐみ, 『Tokyo』(東京: 蒼穹舍).

Visit half a dozen Tokyo photo exhibitions (something easily achieved in a single quarter of the city, in one afternoon), and chances are you’ll see at least one show of street photography. However feeble it might be, it will have more life in it than at least one of the non-street shows. And it could be very good. (One highlight this year: the first ever show by Komase Yutaka, still a student.) And then somehow the good stuff doesn’t get published. (I suppose it just doesn’t sell. People instead want little colour epiphanies, the diaristic, the whimsical, people posed to look blank, Sanai’s latest car, whatever.) Go to a photobookstore, and you’ll see that of the small selection of life-in-the-streets “street” material, much merely presents people just walking down the street toward the photographer, interacting not with the photographer or anyone or anything else, and instead just looking surly, glum or blank. The praise some of its long-term producers get sometimes seems to be for their sheer stamina; I wish them well but their work doesn’t tempt me.

But at last we have here a book of good new street stuff by somebody who’s (fairly) new. Tokyo presents 69 B/W photographs by Ōtsuka Megumi, taken from 2003 to 2012. The book design is minimal: I repeat that it’s by Ōtsuka Megumi as her name doesn’t appear anywhere on the cover or the title page (it’s only within the colophon). She was a student of Moriyama, but his influence is far less obvious than that of Friedlander. What you don’t get here are close-cropped photos of single people (surly, glum or blank) striding toward the camera. There’s always something going on, whether action or composition or both. Ōtsuka (also spelled “Ohtsuka”) has succeeded in putting out a book of Japanese B/W “street” photos that doesn’t make me long for Abe Jun’s Citizens or Kokubyaku nōto in its place. More than that, she even has photos of small kids doing the kind of mildly naughty thing (climbing up a traffic sign, two at a time) that conventional wisdom says (i) never occurs (the kids being glued to their Playstations or otherwise lobotomized) and (ii) would be unphotographable even if it did occur. (Plus she got some of her photos published in the current issue of the nervous Nippon Camera.)

Here’s the book at Sōkyūsha.

Suda Issei, Fushikaden (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 須田一政, 『風姿花伝』(東京: Akio Nagasawa).

Suda Issei, Fushikaden (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 須田一政, 『風姿花伝』(東京: Akio Nagasawa).

In one of the good little essays masquerading as interview responses within the introductory material to the lavish 2011 “Only Photography” book on Suda Issei, Ferdinand Brüggemann rather reluctantly identifies the best section of Suda’s work. It’s the series Fūshi kaden, photographed in the seventies, serialized in Camera Mainichi from December 1975, collected in 1978 in a compact book within the popular series Sonorama shashin sensho, and in 2005 sampled within a utilitarian booklet for a JCII exhibition.

The title? Brüggemann explains, but this, this and (for you readers of Kurdish) this will give hints.

Suda was one of several photographers exploring the countryside of Japan — not a new idea (for example, the Edokko Kimura Ihee had spent a long time in Akita), but one that clearly excited Akiyama Ryōji, Naitō Masatoshi, Kitai, Takanashi, Tsuchida and others in this period as well as Suda. Suda concentrated on festivals, shrines and the like, photographing directly, clearly, and yet somehow elliptically. Hard for a lazy person such as myself to express well, so instead I’ll cop out and point you to a generous sample; and to views of the book itself. There’s variety, as you’ll soon see; but there’s no filler.

Suda not only got a volume within Sonorama shashin sensho, he also got one within the far more selective series Nihon no Shashinka, so he’s been known and respected in Japan for some time. (If he’s only recently become known in the anglosphere, it’s not for lack of advocacy. I suspect that the Euro-American obsession with Provoke is to blame.) But he hasn’t been trendy in Japan until recent years, as the price of the original Fūshi kaden book has joined those of the Sonorama shashin sensho volumes by Araki, Fukase and Moriyama; presumably bought up by people who plan to make a profit selling them to the kind of dimwit who also pays huge sums for books confidently advertised as “flawless” by a seller who admits to not having opened them to look for any flaws. (Pardon the rantlet.) The Sonorama shashin sensho books were good value thirty years ago, but the reproductions are small and poor by today’s standards. That and the high price of the Suda volume make a new edition particularly welcome.

But a new edition this isn’t. Not only does it add photos, it radically rearranges what it inherits from the older book (whose texts, in both Japanese and English, it also drops). For example, what was the first photo in the book is now the last. So think of it as a new and greatly improved selection from the same series.

The reproductions are bigger than they were in 1978, but not as big as in the “Only Photography” book, from which the printing quality differs too: the photos are glossier here and probably for this reason the blacks are slightly blacker. I hesitate to say they’re better, but even if (unlike me) you already have the “Only Photography” book they will not disappoint.

The book’s exterior is surely intended to help justify the book’s horribly high price and to impress; for me, the impression is funereal. No matter: the photographs are fascinating and the reproductions are fine; that’s enough.

There’s a short afterword by Suda, and captions (placename and year), all in both Japanese and English. There’s no explanation of what it is that you’re looking at, merely of when and where it transpired. The photos are enjoyable without this, but I’d be interested to read about them all the same. (In Once a year, itself long overdue for republication, Homer Sykes gave us photos and text.)

Here’s the book at its publisher. It is also available from Japan Exposures.

Suda publishing has recently been on an (overdue) roll. During the last few weeks there have been one and a half other new books by him: Rubber (colour, and very different from Fūshi kaden); and as an appendix to Fūshi kaden, 1975 Miuramisaki. The latter presents a grand total of six (6) photos, all of that one famous snake. Reproduction is superb; price is high. I was sorely tempted, but I already have too many photobooks (each with more than six photos) and so my ten-thousand-yen notes stayed in my pocket.

Tatsumi Naoya, Japan (Warabi, Saitama: Tatsumi Naoya). 辰巳直也, 『日本』(埼玉県蕨市: 辰巳直也). CiNii. The English title appears in the colophon.

Tatsumi Naoya, Japan (Warabi, Saitama: Tatsumi Naoya). 辰巳直也, 『日本』(埼玉県蕨市: 辰巳直也). CiNii. The English title appears in the colophon.

I’ve already seen more than enough photos of the backs (and perhaps the fronts too) of near-naked tattooed men, so the cover of this book wouldn’t have appealed; which is perhaps why it was months before I noticed it within Sōkyūsha’s excellent bookshop. For a self-published Japanese photobook, it was remarkably large and had a refreshingly bold title, so I ignored the tattooed male and picked it up.

The book’s about 30×21 cm; it’s unpaginated but about 18 mm thick. It consists of three parts: “Nishinari 1995–2001”, “Okinawa 2003” and “Shinjuku, 2007–2011”. Nishinari is an impoverished central borough (“ward”) of Osaka, and in this part Tatsumi Naoya presents street portraits of people who I suppose are occasional day labourers or are destitute. Not all the portraits are complete successes but enough are. The Okinawa section presents a good variety of Okinawa, in blazing colour: late Tōmatsu (more) perhaps here meets Uchihara’s Son of a bit (less). The Shinjuku section has (not quite so blazing) colour street photos of the entertainment area, concentrating on the young denizens with their chemically enhanced coiffure and painful shoes; a small percentage of duds here but the great majority have this or that kind of interest. All in all Tatsumi delivers not just volume but content and satisfaction.

Samples of the photos are here on Tatsumi’s site. Here’s the book at Sōkyūsha. It’s also available in various other [physical] bookshops in Japan (listed on Tatsumi’s site); via the internet from Flotsam Books, which takes PayPal but says nothing about sending anything outside Japan.

Want more, better-informed lists? A pile of them are conveniently linked from this Phot(o)lia post. Among them, I only notice one that’s (mostly) devoted to Japanese books: Mark Pearson’s, within (and about two thirds the way down) the BJP listorama. (Intersection of his list and mine: zero books. Indeed, I hadn’t even heard of four of his ten choices, so you now have some idea of the depth of my ignorance.)

PS (31 December): John Sypal has published, not his top ten, not his top three, but his top three of my top ten. I shan’t spoil the fun by divulging what they are; instead, see for yourself. As well as comment, he did what I couldn’t be bothered to do: take and provide photos of his choices (or anyway, of two of them).

PPS (31 January): And another list of favourite Japanese photobooks of 2012.