swell photobooks of 2013

Posted: 14/12/2013 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists, Arimoto Shinya, Kurata Seiji, Onaka Kōji, photobooks from Japan, Suda Issei, Watabe Yūkichi 3 CommentsApproaching the end of another year: it’s the season for photobooks roasting on an open fire, and lots more mutual encouragement to acquire more stuff and make the year’s consumption more conspicuous. I’m tempted to do a world survey, but I haven’t seen enough of what my fellow bloggers prattle about, let alone of the many more books that largely go unmentioned but that sound interesting (example). So I’ll do a _Valerian and look at Japan and not sekai (as the rest of the world is called hereabouts).

I thought that Abe Jun’s Black and white notebook 2 came out this year, but its colophon tells me December ’12. So that’s out. I solemnly swear that all the below are from 2013, honest. (Except for one that might be older than you are, but this is clearly so identified.)

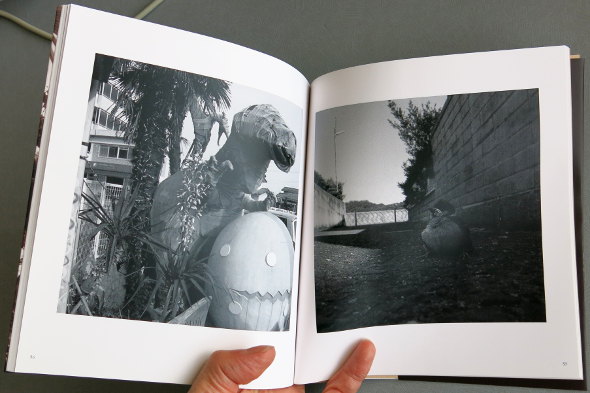

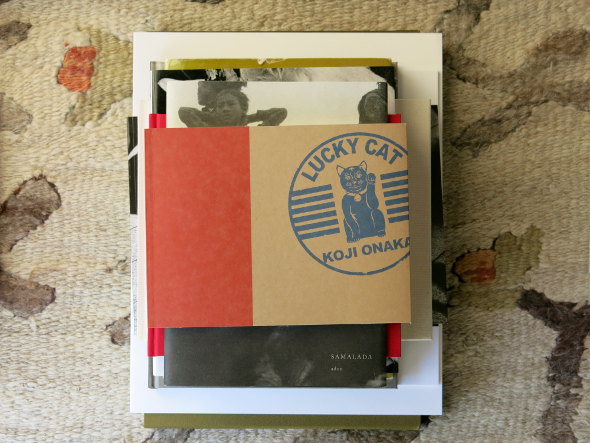

Onaka Kōji, Lucky cat

The lucky cat of the title is the maneki-neko; but fear not, there are only two of these in the book. Both are distinctly old and worn, as is just about everything else depicted in this collection of musty and rusty nooks of Japan, each somehow with its attractions.

Plenty of photos of this here at Onaka’s site, here at atsushisaito’s, and here at Josef Chladek’s. Here’s a video flip-through of the book.

Onaka Kōji (尾仲浩二). Lucky cat. Matatabi Library. No ISBN. I think “Matatabi Library” means Onaka. (Trivia lovers: matatabi means this.) Anyway, the book is available from the man himself (rather stiff postage charges) as well as booksellers.

(For this and the other books below, potentially helpful booksellers are linked to at the bottom of this post.)

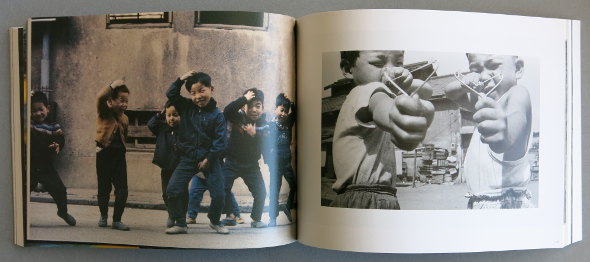

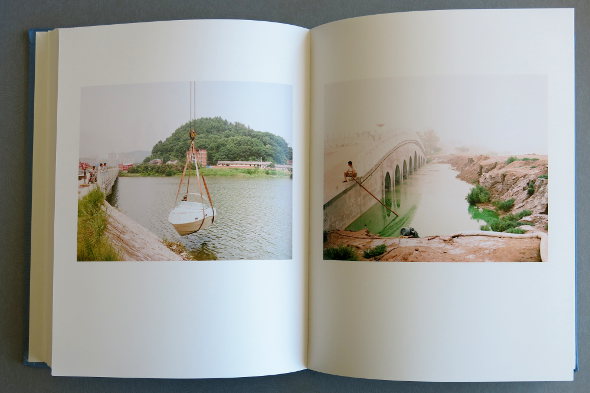

Adou, Samalada

Adou was a new (Chinese) name to me when I saw a show of his work this year at Zen Foto Gallery (Roppongi). The prints were big and murky (neither of which normally attracts me); S(h)amalada (here) looked bleak, but the photographs were compelling all the same.

You can see them on Adou’s site and also here at M97 Gallery (Shanghai).

Adou (阿斗). Samalada = 沙馬拉達. Zen Foto Gallery. ISBN 978-4-905453-28-4.

The booklet (shown above) from Zen seems to be at least the third major publication of these photos: they have also constituted one volume out of the five of a boxed set, Outward expressions, inward reflections (外象, here); and earlier this year the larger half of a book, Adou & Samalada (阿斗 · 沙马拉达, here). I haven’t seen the former, but the printing in the latter is so different from that in the Zen booklet that somebody (and not only a collector fetishist) might actually want both. If (more sensibly) you want just one, perhaps get the Zen version if you’re in Japan, one of the two Chinese versions if you’re in China, and compare airmail charges etc if you’re elsewhere.

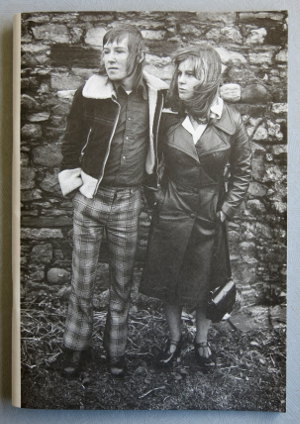

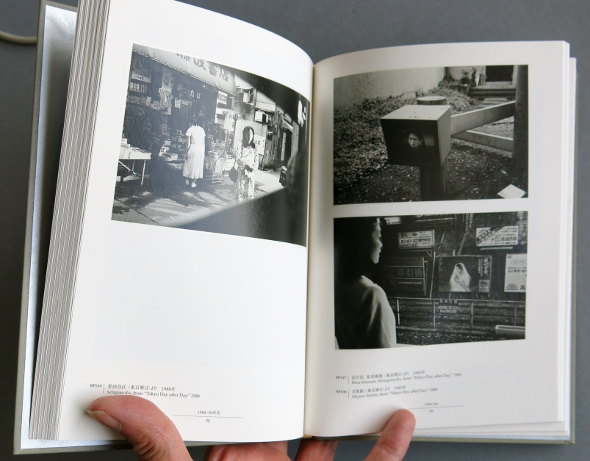

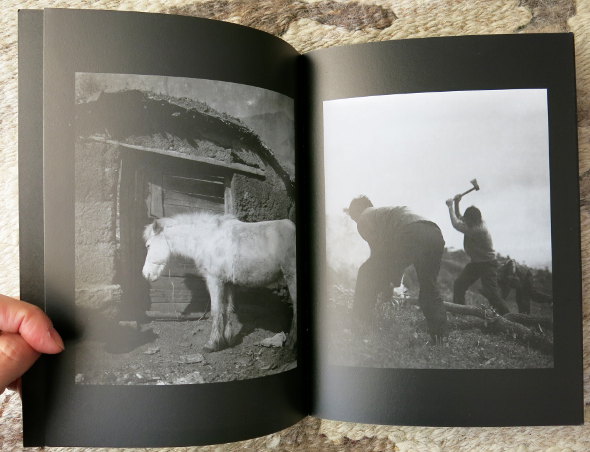

Suda Issei, Early works 1970–1975

Here’s one for you rich people! Yes, over two hundred photos taken by Suda in his early thirties (and thus allowing for at least one volume of very early works). A lot of these appeared in photo magazines at the time. So let’s correct the above: this horribly expensive book is for the middle-income, the rich being able to afford places large enough to house complete runs of 1970s’ Asahi Camera and its rivals. Some is rather “street”, a lot is close to Fūshi kaden. Most is 35mm (or anyway isn’t square). Not every plate is of a five-star photo, but enough are, and the reproduction is excellent.

Here’s one for you rich people! Yes, over two hundred photos taken by Suda in his early thirties (and thus allowing for at least one volume of very early works). A lot of these appeared in photo magazines at the time. So let’s correct the above: this horribly expensive book is for the middle-income, the rich being able to afford places large enough to house complete runs of 1970s’ Asahi Camera and its rivals. Some is rather “street”, a lot is close to Fūshi kaden. Most is 35mm (or anyway isn’t square). Not every plate is of a five-star photo, but enough are, and the reproduction is excellent.

As if there weren’t already enough gimmickry in the wacky world of photobooks, this one comes with a choice of five cover photos.

Suda Issei (須田一政). Early works 1970–1975. Akio Nagasawa. No ISBN.

The same publisher recently decided that its Fūshi kaden wasn’t expensive enough already, and raised the price by 50%. That might happen with this book too.

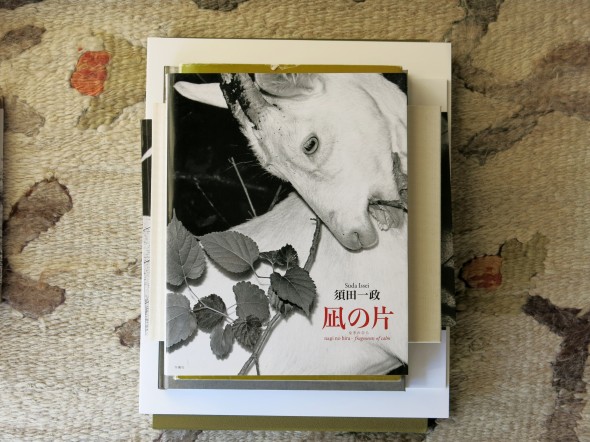

Suda Issei, Fragments of calm

The Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography is of course a wonderful institution but it has recently taken to devoting an entire floor to this or that exhibition of overly reproduced or modishly boring photos. But now and again it has an excellent exhibition of the first-rate; and this year’s big Suda show was one. (With a modest entry price too.)

The Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography is of course a wonderful institution but it has recently taken to devoting an entire floor to this or that exhibition of overly reproduced or modishly boring photos. But now and again it has an excellent exhibition of the first-rate; and this year’s big Suda show was one. (With a modest entry price too.)

And here’s the catalogue. The idea seems to have been that of a tolerably good package of decently sized plates, held down to a very palatable price. So many pages are rather cramped, the printing quality is distinctly twentieth-century, and the result would never win any photobook award. Don’t complain, because you get decent reproductions of over two hundred good photos at a keen price.

(For those interested in these matters: Suda seems to have signed hundreds if not thousands of copies, which, as is normal in Japan, go for the list price. Indeed, a recent book by Suda that doesn’t have his signature might be a “collectibly” rare variant.)

Here’s a video flip-through of the book.

Suda Issei (須田一政). Fragments of calm = 凪の片. Tōseisha. ISBN 978-4-88773-145-5.

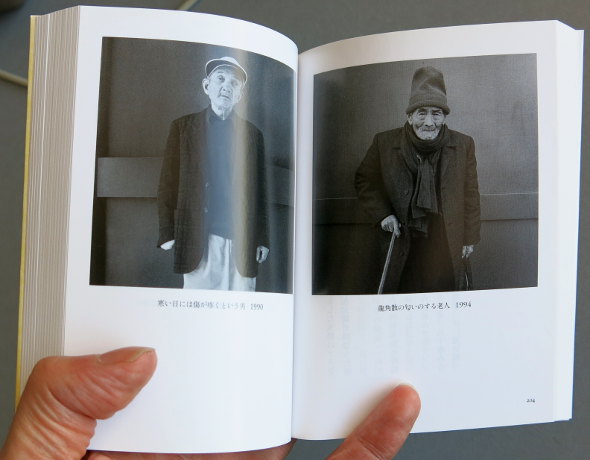

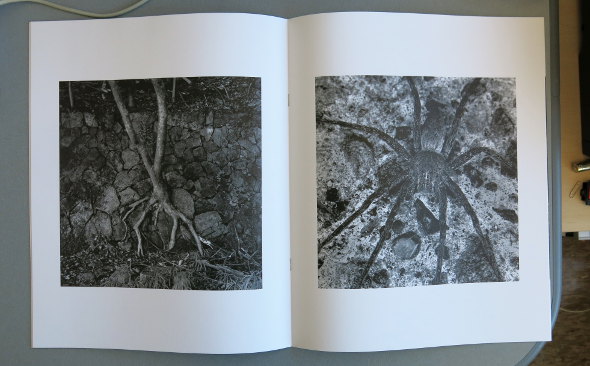

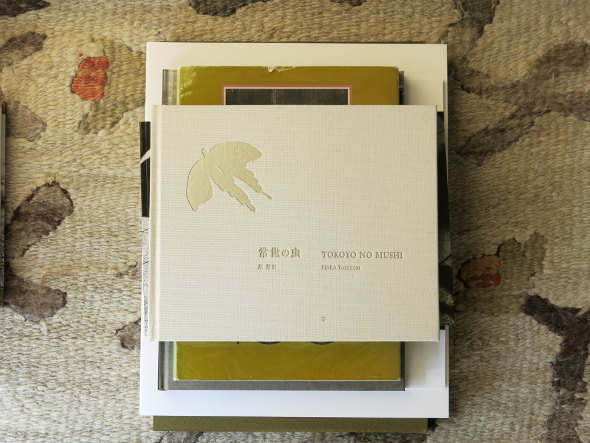

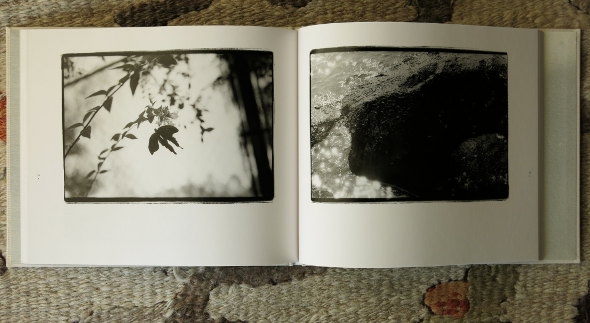

Hara Yoshiichi, Tokoyo no mushi

The title means something like “eternal insects” or “insects from the realm of the dead”, and a prefatory note by Hara says he’s heard stories that after death people are transformed into insects. There follow photos incorporating insects, photos of (a non-entomologist human’s idea of) an insect’s view of the human world, photos alluding to birth and to death, photos of models of the human world at a (large) insect’s scale, and more. The religious may make sense of this; I just enjoy the results in my atheistic way.

The title means something like “eternal insects” or “insects from the realm of the dead”, and a prefatory note by Hara says he’s heard stories that after death people are transformed into insects. There follow photos incorporating insects, photos of (a non-entomologist human’s idea of) an insect’s view of the human world, photos alluding to birth and to death, photos of models of the human world at a (large) insect’s scale, and more. The religious may make sense of this; I just enjoy the results in my atheistic way.

There are plenty of photos of this book here on Josef Chladek’s site and here on atsushisaito’s.

Hara Yoshiichi (原芳市). Tokoyo no mushi = 常世の虫. Sōkyūsha. No ISBN.

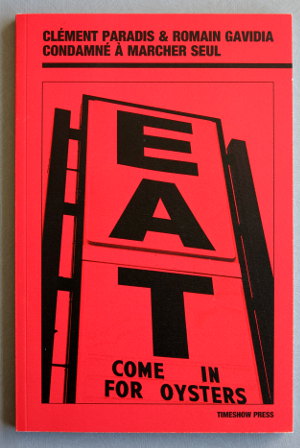

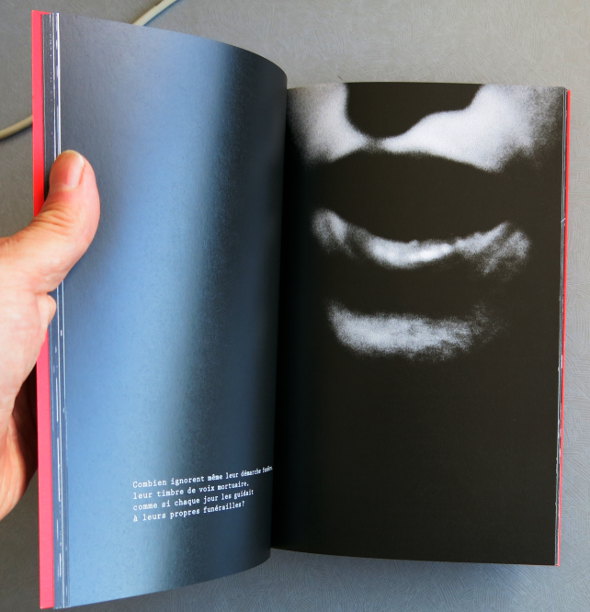

Nuno Moreira, State of mind

This book is going to puzzle whichever poor librarian is the first to provide Worldcat with a record for it: no publisher is specified, let alone place of publication. Actually it’s published by its creator, who (mostly) lives in Tokyo; so despite its Portuguese ISBN it’s at least as Japanese as it is Portuguese or anything else.

This book is going to puzzle whichever poor librarian is the first to provide Worldcat with a record for it: no publisher is specified, let alone place of publication. Actually it’s published by its creator, who (mostly) lives in Tokyo; so despite its Portuguese ISBN it’s at least as Japanese as it is Portuguese or anything else.

It’s a collection of “solitary moments of disconnection” (in the photographer’s words), or perhaps of indecisive moments (not his words). We see individuals thinking, individuals not thinking, scenes likely to start one thinking — yes, it’s free-ranging. There’s even the occasional crowd, though the individual seems in a pocket of space within it. And many pleasing plays of light and shadow.

Many photos from the book here; and here’s a video flip-through of the book.

The printing could be better, but it does the job. (Certainly the book makes a refreshing change from the piles of exquisitely printed books of boring photos.)

Nuno Moreira. State of mind. Self-published. ISBN 978-989-20-4151-3. Available from the man himself.

Suda Issei, Waga Tōkyō 100

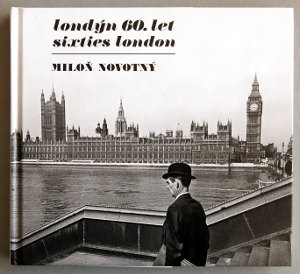

Looking a bit tired, with its dated cover design? Well yes — it’s over thirty years old.

And yes, it’s Suda again. The title can be loosely translated as “a hundred views of my Tokyo”. More square B/W, from shortly after what’s in Fūshi kaden, and similar to that and almost as good. The book shown above is printed well for its time, there are seemingly thousands of copies available, and (other than from the dealers with the slickest websites) these are cheap.

Or so I had thought. But I now realize that copies now cost about three times as much as they did just three years or so ago when I bought mine. (At hermanos Maggs, ten times as much.)

And so it makes sense for a new edition to come out. But this is a bit on the pricey side. If I lost my copy of the old one I don’t know which edition I’d replace it with. For those who don’t happen to be in Japan, a copy of the new edition (details below) would be easier to obtain than a reasonably priced copy of the old one.

The new edition is a kind of hardback/paperback hybrid. (Unkindly, it’s like a hardback whose front hinge has been neatly sliced through.) It’s shorn of a lot of the (Japanese) text of the first edition, but it has some new text in Japanese and English. And it’s well printed. The plates are (trivially) smaller than those in the original. Although the sequence of plates is different, I think that the same hundred are used in both.

Suda Issei (須田一政). Waga Tokyo 100 = わが東京100. Zen Foto Gallery. ISBN 9784905453314 (I think). The price is being held down for some time, whereupon it will jump 25% or so (to about half of the current price of Early works 1970–1975).

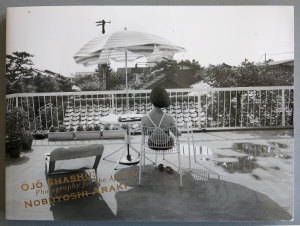

Watabe Yūkichi, Stakeout diary

You know the story, or bits of it: For twenty days in 1958 a youngish photographer was allowed to photograph two cops hunting for a suspect in a grisly murder; some of the resulting photographs were published in a magazine in 1958, they were then largely forgotten; somebody bought prints half a century later and turned them into the only non-Japanese book by this “unknown” photographer; the book was much feted outside Japan (and an unusual and expensive import within).

You know the story, or bits of it: For twenty days in 1958 a youngish photographer was allowed to photograph two cops hunting for a suspect in a grisly murder; some of the resulting photographs were published in a magazine in 1958, they were then largely forgotten; somebody bought prints half a century later and turned them into the only non-Japanese book by this “unknown” photographer; the book was much feted outside Japan (and an unusual and expensive import within).

Well, here’s a Japanese edition, from prints freshly made by Murakoshi Toshiya; and from a brand new publisher, Roshin Books. It has a larger format than A criminal investigation and contains photos that aren’t in that; and the package doesn’t try so hard to be remarkable but I prefer it. “Landscape” photos are either broken across the gutter or squeezed into half a page; I’d have been happier if they’d been rotated to fill the single page. But a large percentage are “portrait”, and this is a fine book.

Plenty of photos of this are here at atsushisaito’s site, and here’s a video flip-through.

This book too has front cover variants. All variants of the regular version are sold out (at Roshin, if not necessarily at retailers), but Roshin still has copies of the version that comes with a print.

Watabe Yūkichi (渡部雄吉). Stakeout diary = 張り込み日記. Roshin Books. ISBN 978-4-9907230-0-2.

I’m looking forward to the appearance in January of Roshin’s second book. (And I wonder if there’ll be a second book from Plump Worm Factory, publisher of Murakoshi’s Prayer & bark.)

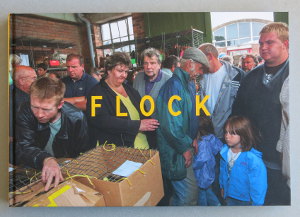

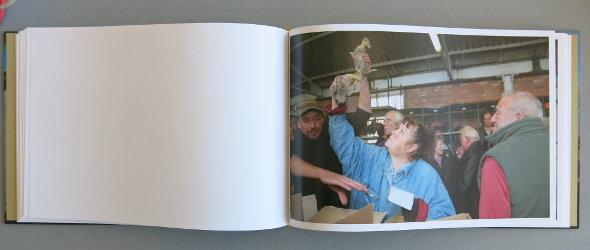

Kai Keijirō, Shrove Tuesday

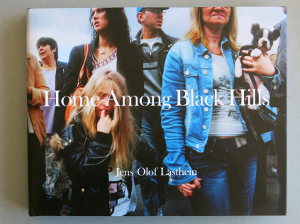

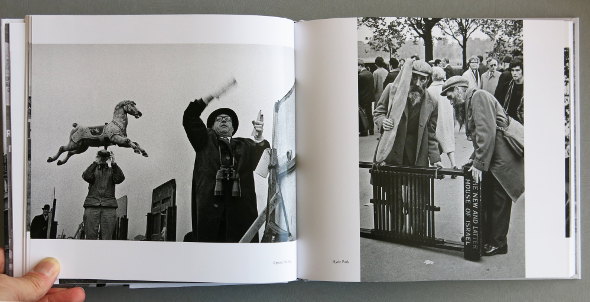

The photos here are alarming. They’re obviously of somewhere in Britain. There are many young and middle-aged heads glaring, gasping for breath, or just looking lost; they’re all male, many are shaven, they’re all “white”. Yet there are no flags of Ingerland and so it can’t be the EDL.

The photos here are alarming. They’re obviously of somewhere in Britain. There are many young and middle-aged heads glaring, gasping for breath, or just looking lost; they’re all male, many are shaven, they’re all “white”. Yet there are no flags of Ingerland and so it can’t be the EDL.

It’s sport(s), but far from what you might see on the telly. It is instead the Shrovetide football match of Ashbourne (Derbyshire): one of the most physical of Britain’s quaint provincial customs. Just good testosterone-powered fun! Somewhere in the middle of all this, there must be a ball — though since most of the players themselves are just blindly following other players (and trying to infer who’s on which side; there are no uniforms), perhaps there isn’t after all and instead it’s far away.

All very exciting, and I hope that Kai follows it up with more revelations of the exotic occident (but pauses before his camera or head collides with a boot).

Kai Keijirō (甲斐啓二郎). Shrove Tuesday. Totem Pole Photo Gallery. No ISBN. Available from TPPG if you go there in person.

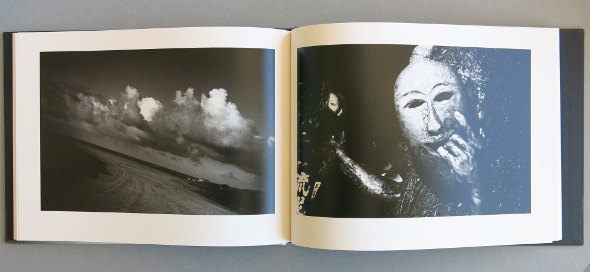

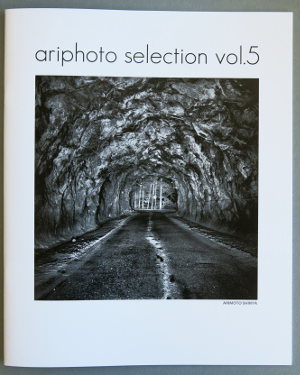

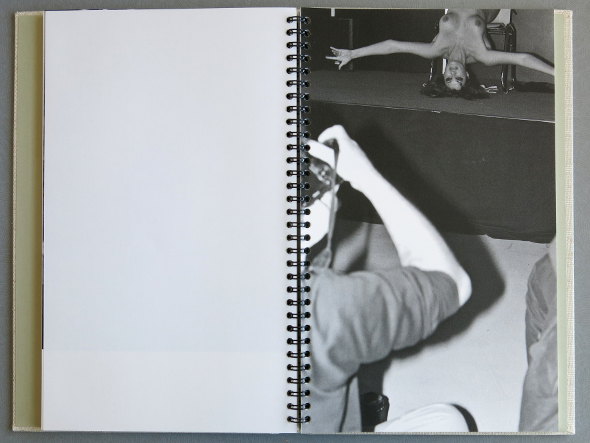

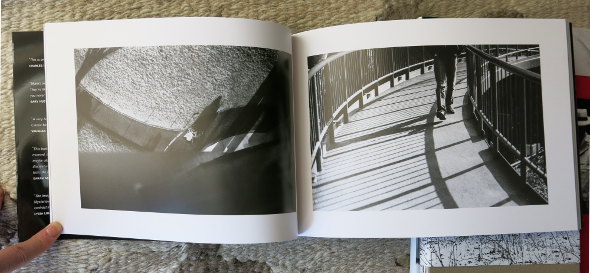

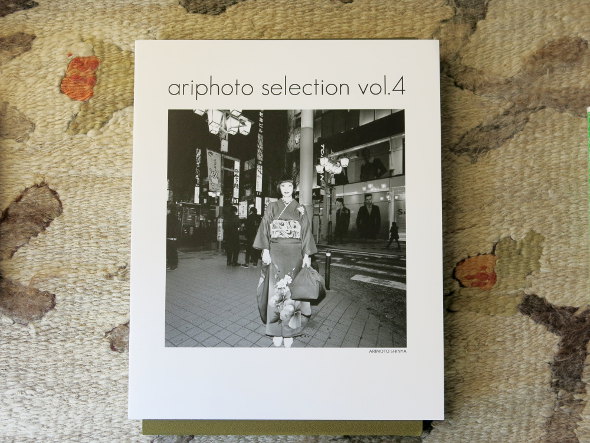

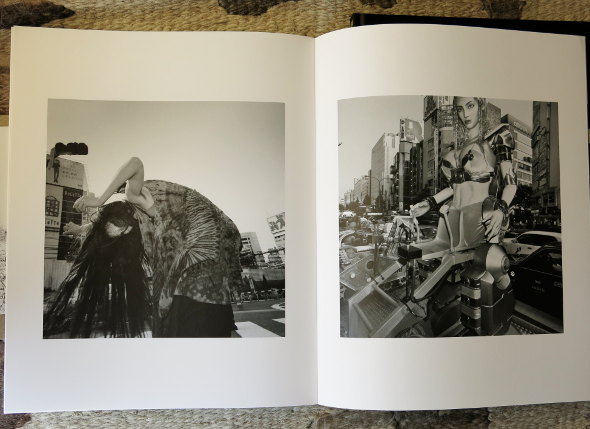

Arimoto Shinya, Ariphoto selection vol. 4

The fourth fascicle of . . . I don’t quite know what, after the third (of Tibet) showed I was wrong to think it was Tokyo.

The fourth fascicle of . . . I don’t quite know what, after the third (of Tibet) showed I was wrong to think it was Tokyo.

They’re probably not fascicles at all, and should be enjoyed independently. And enjoyable they are. They’re “street”, street portraits, things seen in streets. In the first three photos in vol. 4, an elderly, heavily bejewelled gent fishes change from that relic of the last century, a payphone; a contortionist performs in mufti, no, she’s just a normal girl trying to shake a tiny stone out of her boot; a young transsexual happily displays her new breasts to a friend (out in the street, in daylight). True, there aren’t many more photos, but each is big and well printed.

Arimoto Shinya (有元伸也). Ariphoto selection vol. 4. Totem Pole Photo Gallery. No ISBN. Available from TPPG if you go there in person, or from the man himself over the interweb. Or from PH, which still seems to have copies of vol. 3 (out of stock elsewhere).

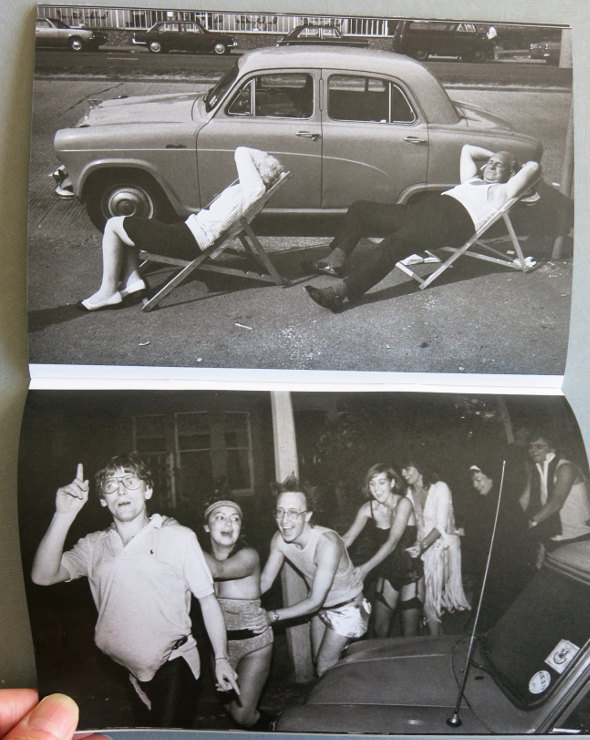

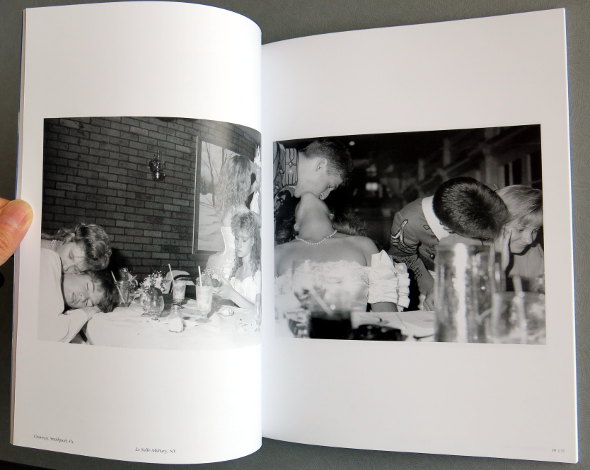

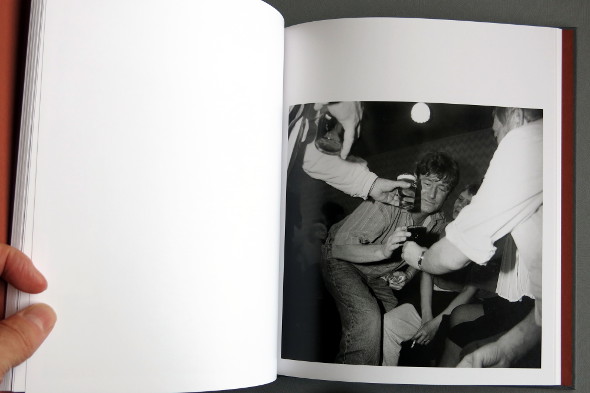

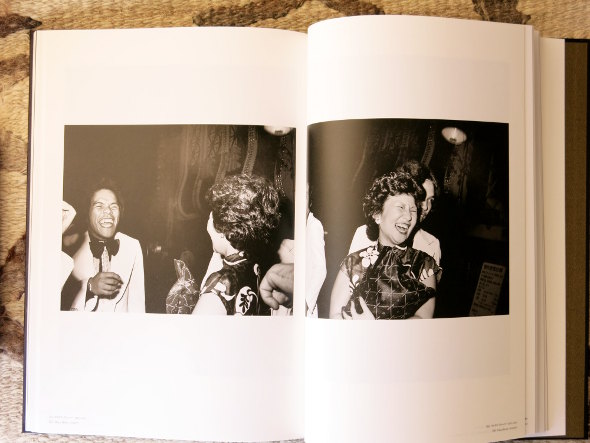

Kurata Seiji, Flash up

Such an opulent slipcase. It looks like a lot of the big photobooks from the sixties that gather dust in Tokyo’s used bookshops: you see a familiar name on the spine — Iwamiya or Midorikawa, perhaps — and look inside to discover that it’s all about Japanese gardens, is in muddy colours, is deadly dull, and cost 38,000 yen (of 1960s money) when new. (Did companies buy them up to hand them out as trophies?)

But a gaudy kind of opulence is appropriate here. Cabaret packaging, indeed (preferably reeking of old cigarette smoke). Because it’s for:

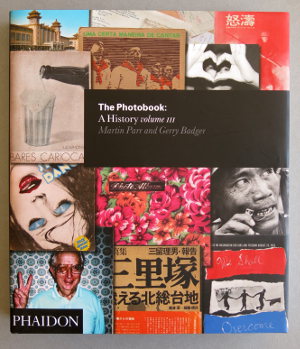

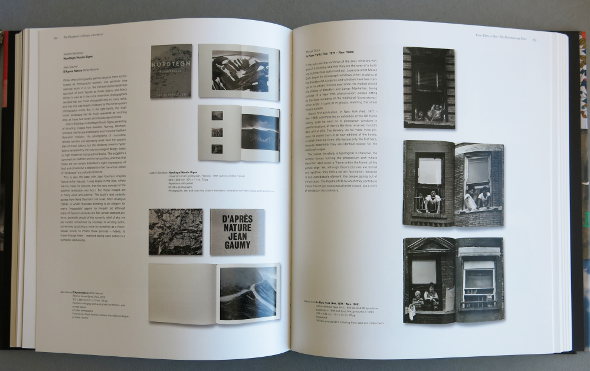

Yes, this is a long overdue second edition of a boss photobook. (Don’t recognize the title? Check your Parr ’n’ Badger, I:305.)

No blurring or other Provoke-ative devices here; instead, it’s a 6×7 or 6×9 and flashgun used fluently in Weegee/Moriyama territory, delivering more immediacy and happy surprises than most photographers can manage outdoors in daylight. The most Weegee-like photos are gruesome but the others are among the most enjoyable photos anywhere.

No blurring or other Provoke-ative devices here; instead, it’s a 6×7 or 6×9 and flashgun used fluently in Weegee/Moriyama territory, delivering more immediacy and happy surprises than most photographers can manage outdoors in daylight. The most Weegee-like photos are gruesome but the others are among the most enjoyable photos anywhere.

And more prints, and bigger ones, than you’ll find in the first edition. Which anyway costs about twice as much as this second one costs — which is a lot, but justifiably so. (NB the new edition is so big and heavy that postage could be considerable.)

Plenty of photos of this here at atsushisaito’s blog.

Kurata Seiji (倉田精二). Flash up. Zen Foto Gallery. No ISBN.

Plus special pats on the back for three books that I didn’t buy and therefore can’t plonk on the rug in front of my camera:

Watanave Kazuki, Hito. The title means “people” (or “person”), and the book follows pigs from happy life to merchandise: in colour, with all that this entails. It’s neither sensationalist nor sparing, and comes with thoughtful afterwords (in English as well as Japanese) by two of the men whose work is depicted. Here it is at atsushisaito’s blog. An admirable book, one I’d recommend for any library, but (sorry) not one I’d often want to look at, and so space constraints rule it out.

Watanave (Watanabe) Kazuki (渡辺一城), Hito (人). 4×5 Shi no go. ISBN 9784990559816. According to a page within the website of the publisher (a group or company of four photographers), the address to ask about it is contact [at] shinogo.com

Kōriyama Sōichirō, Fukushima. Straight but thoughtful documentary photography of the effect (social and only indirectly medical) of radiation in Fukushima. Slim, but well done, informative, excellently printed, and modestly priced. I’m not getting a copy only because I OD’d on similar (if mostly inferior) books last year, and because plenty of libraries here should have it.

郡山総一郎, Fukushima × フクシマ × 福島. 新日本出版社. ISBN 978-4-406-05673-1.

I don’t remember Kōriyama’s book as providing English captions, but there are hints here that it does (and that it has an alternative title, Fukushima black rain).

Shiga Lieko, Rasen kaigan: Album. The ghost of Nickolas Muray appears to the young Naitō Masatoshi, prods him to watch Eraserhead and gives him some bricks of infrared Ektachrome. Or something like that. This book, which you’ll have read about already, has some fascinating photos (the ash or snow covering the car interior, the glittering disposable plates, etc). I suppose it’s something like a feature film on paper . . . but a feature film fits handily into a DVD (or of course a few square nanometres of a hard drive) whereas this is a considerable slab of dead tree. And while I might flick through the (many) photos of stones, I wouldn’t want to examine them. Also, when I open the book wide to get a good view of the photos across double-page spreads, the spine makes an ominous cracking sound. But yes, the best of it is very good, so I look forward to Shiga’s Greatest hits.

There are some patterns here:

- Every one of the book(let)s above is published in Tokyo (except perhaps Lucky cat). Seigensha and (I think) Foil are based in Kyoto, but recently haven’t excited me. Vacuum Press (Osaka) has been quiet, Mole (Hakodate) is either dead or long dormant, and I haven’t noticed anything new like Kojima Ichiro photographs (nominally published in Tokyo but really a production of Aomori).

- Mostly B/W. This is odd: Most of the new non-Japanese books that interest me are colour.

- Overwhelmingly by men. Very bizarre, as plenty of the new non-Japanese books that interest me are by women.

- Mostly by old geezers (if not necessarily old when they took the photos). Really sad, this. I do see some excellent little shows by young photographers.

- Skewed toward one photographer, Suda. If any septuagenarian Japanese photographer merited a raise in exposure, it was him. I don’t begrudge him it at all. Still, it’s amusing to see the star-making system in action. (And of course I’ve added my unimportant croaks to the chorus.) This year there’ve also been two other books by Suda that I haven’t mentioned above, and in the next few weeks there’ll be Tokyokei and, I believe, one more. Good! But . . . enough for now? Attention Roland Angst: Could you now please (re)discover Nagano Shigeichi?

Again inspired by _Valerian, some (more) words on books I didn’t buy:

Araki seems to put out a new book every couple of weeks, and I only look into a copy in a bookshop if its cover is both unfamiliar and arresting. Some I didn’t notice at all. Shi-shōsetsu (死小説, perhaps also titled Death novel) would have been one of these. I normally don’t bother looking at anything by Moriyama unless somebody is particularly enthusiastic about it, but View from the laboratory (実験室からの眺め, on Niépce) looks interesting and I look forward to examining it. Kawauchi’s Ametsuchi seems to have some good material, but I wasn’t much tempted even by a pile of half-price copies (here) of the Japanese edition, in part because this shares the perverse design of the Aperture version.

And then there are — I infer from word of Einmal ist keinmal — more books whose existence I haven’t even noticed.

Plus my taste is probably defective.

If you’re in Japan, you’ll probably already know where to look for books; if you aren’t, duckduckgo for them. If you want new books to be sent out of Japan, aside from tips above there’s Shashasha, Flotsam and Book of Days (none of which I’ve bought from), and Japan Exposures (which I have); if you want used books there’s Mandarake.

You’ll find more “best of 2013” lists here.

PS (28 Dec): A disproportionate number of the most rewarding among these are by some bloke in Eugene. And among them — well, see for yourself.

great photobooks of 2013 that I didn’t buy

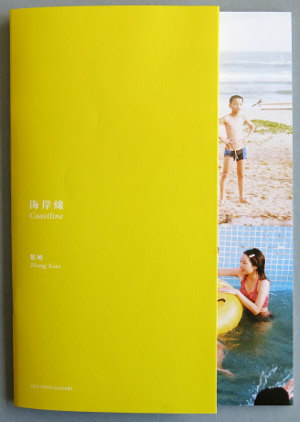

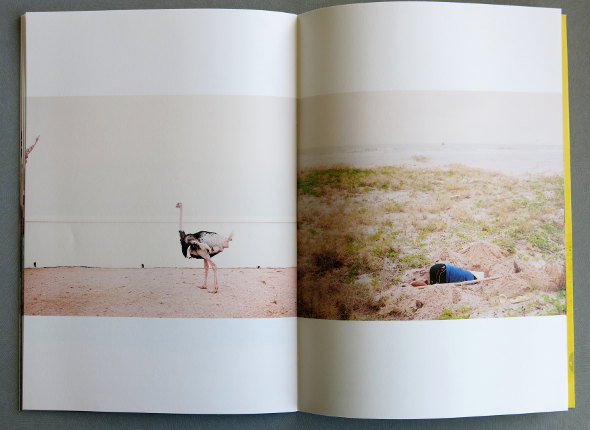

Posted: 26/11/2013 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists, Kurata Seiji, Suda Issei, Zhang Xiao 7 CommentsCarolyn Drake, Two rivers. Apparently promoted via Kickstarter during one of those long periods when I avoid Kickstarter because the last screenfuls I saw were too dreary. Now that I learn of it, just months after publication, already out of print. This is a great shame as the subject is most interesting and what JPEGs I’ve seen of the photos look excellent. I hope Drake follows the Sochi Project in bringing out a second edition — perhaps a regular paperback so as not to upset collectors thrilled by the (artistically!) wrong-sized cover of the first edition.

Kurata Seiji, Flash up. The original is a routine sort of paperback that contains the most enjoyable photos ever of this (rather overdone) sleaze genre. (Don’t be put off by the front cover of the original, which oddly has one of the least interesting photos in the book.) One of my rare intelligent bookshop decisions decades ago was to buy it when it came out. My copy resides in an actual bookshelf with glass doors, and when I want to look at it I have to shovel piles of other books off the floor in order to open and close these doors. I haven’t seen the new edition, which may be worth its high price; but I think I’ll just keep on shovelling.

Martin Kollar, Field trip. Though I was disappointed by Kollar’s Cahier I liked his Nothing special. JPEGs of the content of the new book looked intriguing and I recently came across a copy. The photos are just as good as I’d hoped. A lot are mystifying, which is fine with me. But for the price, I want explanations after I’ve enjoyed the mystification. True, explanatory text isn’t a trendy notion; but David Goldblatt for one provides explanations and these don’t seem to deter potential buyers or indeed award committees. If Kollar rectifies the omission (and all this needs is a web page), then I’ll buy a copy.

Seto Masato, Cesium 137Cs. Anthropomorphic branches and other mysteries of the freshly irradiated forest, a fascinating example of a kind of book that usually holds little interest for me. Expensive, but yes I can stump up the cash. It’s B4 format, which may well be justified — but I’ve simply run out of niches for the storage of books that big. ….. PS There’s currently a 20% discount if you buy the via the internet from Place M and a 30% discount on the book if you buy it at Place M.

Suda Issei, Waga Tokyo 100. Good stuff in this book, but I have one of the thousands of copies of the original, whose printing quality is tolerable.

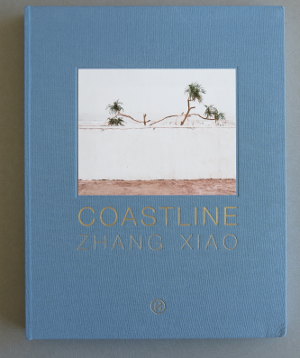

Zhang Xiao, Shangxi. I bought Zhang’s two previous books and enjoy them both. I don’t know how many photos there are in this third one, but the photos I’ve seen of it make it look slim, and its RRP is $75 even before postage is added. And it’s got an (artistically!) wrong-sized cover. Zhang kindly provides thirty of the photos on his website, so I’ll enjoy them there. For his fourth book I hope he returns to Jiazazhi, which did a very handsome job for his They, and which sent me a copy efficiently and inexpensively.

a tassel for Kassel

Posted: 20/09/2013 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists, Arnold van Bruggen, Rob Hornstra, Sochi Project Leave a commentThe Photobook Award 2013 contenders are selected by a jury comprising renowned photography experts from around the world. Some of the choices are good, but some of the others . . . oh dear.

Photobook selection is more important than etiquette, so I gatecrashed:

Yes, Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen, The secret history of Khava Gaisanova and the north Caucasus. Or if you’re lucky enough to be able to read Dutch, then their De geheime geschiedenis van Khava Gaisanova en de Noord-Kaukasus instead, with a €5 rebate.

Buy it, read it. It has lots of Arnold’s excellent text. Yes, though some of my distinguished co-jurors choose books suitable for adorning bedside tables in department stores (and Machiguchi congratulates himself with a book designed by Machiguchi), this book requires actual reading. You know you can do it for book-books, you can do it for photobooks too.

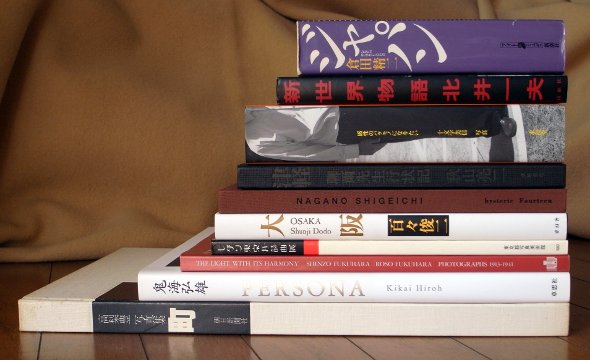

top Japanese photobooks of 2012

Posted: 28/12/2012 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists, Arimoto Shinya, Dodo Shunji, Hashimoto Katsuhiko, Hatsuzawa Ari, Ikazaki Shinobu, Kimura Hajime, Ogawa Takayuki, photobooks from Japan, Suda Issei, Tatsumi Naoya, Ōtsuka Megumi 6 CommentsInability to produce a list of the year’s best (from anywhere) doesn’t stop me from producing a list of the year’s best from Japan. For 2011 this was difficult, but this time around there’s a lot more good stuff (or I searched for it more energetically). And two dismissive messages I received a couple of weeks ago (“Top 10 lists, ugh!” and “the whole ‘best of’ thing leaves me a bit nauseous”) meant I just had to make a list. Even if you’re sufficiently insane to trust my judgment, the list can’t be authoritative: I haven’t yet got around to looking at Hamaura Shū’s Sorane and Watanabe Satoru’s Da.gasita. (Among what I didn’t bother to look at, there’s perhaps half of the product of the Araki and Moriyama industries — even putting aside the monumental contribution from Aperture — and of course a pile of books whose covers either exuded mere prettiness or just looked too boringly trendy.)

Big omissions:

- Arita Taiji’s First born. I remember skipping those pages of Camera Mainichi devoted to the series decades ago, and now that a book is at last available it still doesn’t click. But plenty of people whose opinions I value do appreciate it, so take a look.

- What’s arguably the year’s most outstanding Japanese photobook: I exclude Obara Kazuma’s book Reset: Beyond Fukushima merely because it happens not to be Japanese. (Though perhaps it’s not Japanese by necessity. Would any Japanese publisher have had the guts and energy to produce it?)

The order of what follows is merely alphabetical by photographer. I give Worldcat and CiNii links where I could find them; if I don’t give an ISBN then there isn’t one. I also give tips on where to buy. (I know the people who run Japan Exposures, but not well. I have no relation whatever to Bookofdays or Flotsam.) Where there’s no particular tip, you could try this service.

Arimoto Shinya, Ariphoto selection vol. 3 (Tokyo: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). 有元伸也, 『Ariphoto selection vol. 3』(東京: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). CiNii. The third fascicle (“volume” is rather a misnomer) of what I’d presumed was going to be a Shinjuku anthology but turns out not to be. Arimoto Shinya and his Rolleiflex returned to Tibet in 2009 (a decade after his Tibet book was published), and here’s the result. It’s 36.5×29.5 cm, containing just 16 B/W photographs, the majority of which are portraits. Like the two previous fascicles, it’s as slim and inexpensive as a zine but as well printed as a real photobook. You could buy two copies, cut them up and frame the pages for your personal Arimoto exhibition.

Arimoto Shinya, Ariphoto selection vol. 3 (Tokyo: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). 有元伸也, 『Ariphoto selection vol. 3』(東京: Totem Pole Photo Gallery). CiNii. The third fascicle (“volume” is rather a misnomer) of what I’d presumed was going to be a Shinjuku anthology but turns out not to be. Arimoto Shinya and his Rolleiflex returned to Tibet in 2009 (a decade after his Tibet book was published), and here’s the result. It’s 36.5×29.5 cm, containing just 16 B/W photographs, the majority of which are portraits. Like the two previous fascicles, it’s as slim and inexpensive as a zine but as well printed as a real photobook. You could buy two copies, cut them up and frame the pages for your personal Arimoto exhibition.

Available directly from the photographer (as is vol. 2).

Dodo Shunji, Horizon far and away 1968–1977 (Tokyo: Akaaka-sha). 百々俊二, 『遙かなる地平 1968–1977』(東京: 赤々舎). ISBN 978-4-903545-87-5. CiNii, Worldcat. (This photo shows (A) the book as normally sold new in Japan: a translucent yellow cover goes over an obi which goes over (B) a very different cover; and (B) is how the book is sometimes advertised and perhaps also sold. Don’t worry; it’s the same book.)

Dodo Shunji, Horizon far and away 1968–1977 (Tokyo: Akaaka-sha). 百々俊二, 『遙かなる地平 1968–1977』(東京: 赤々舎). ISBN 978-4-903545-87-5. CiNii, Worldcat. (This photo shows (A) the book as normally sold new in Japan: a translucent yellow cover goes over an obi which goes over (B) a very different cover; and (B) is how the book is sometimes advertised and perhaps also sold. Don’t worry; it’s the same book.)

The photos in Dodo Shunji’s earliest photobook (1986) are lively but copies of this are elusive; the photos in his second (1995) are never less than workmanlike but for me the spark had gone and wouldn’t return until Osaka (2010). Yet in magazines and so on there have been glimpses of early, energetic work. At last here it is, anthologized in well over four hundred pages. It’s in twenty-six lettered sections, A to Z: we get student riots, down-at-heel quarters of Osaka, Dodo’s fiancée-then-wife, the infant Dodo Arata, protests close to US military bases, Americans close to these bases, short trips to London, Pusan, Hokkaidō, and more. It ends with the newborn Dodo Takeshi.

The subject matter and mood put this together with what Araki (minus repetition and obsessions), Tōmatsu and Kitai were doing at about the same time. A lot of photos are included on the strength of their atmosphere. Nobody would want to plod from start to end of this collection of three-hundred-plus photos — you’d take it in (diverse) instalments. It’s a book full of energy, and a delight.

All the photos are in B/W; but a variety of papers are used, the particular paper chosen to match the particular story. Each section is titled in Japanese and English. An interview that runs to almost twenty pages and in which Dodo comments on each lettered section is in Japanese only; but a postscript, potted bio and so on are in English too. It’s on the expensive side for a photobook of 19×26 cm format, but then it has a lot of pages.

The book is here at its publisher, and here at Sōkyūsha; if you’re outside Japan, it’s more simply available from Japan Exposures or from Bookofdays.

Hashimoto Katsuhiko. The other scenery. (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 橋本勝彦, 『もうひとつの風景』(東京: 蒼穹舍). (The English title only appears inconspicuously within the colophon; the reading of the Japanese title is Mō hitotsu no fūkei.) CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Hashimoto Katsuhiko. The other scenery. (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 橋本勝彦, 『もうひとつの風景』(東京: 蒼穹舍). (The English title only appears inconspicuously within the colophon; the reading of the Japanese title is Mō hitotsu no fūkei.) CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

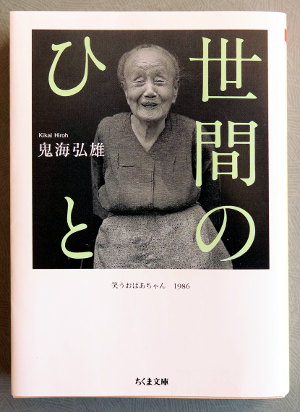

Another of (seemingly) dozens of elegantly packaged hardbacks from this publisher. The photographer finances the enterprise; and although there are editorial standards, a lot of these books are honourable and pleasant but no more. This one is squarely in the genre of views of untended corners of lived-in Japan, without people present. Perhaps the genre’s best-known exponent (for Tokyo) is Kikai Hiroh, but other good books include Fujita Mitsuru’s Zaisyo (the built-up countryside). (Such photos are also used for filler around photos with people in them.) Do we need yet more examples of the genre? No we don’t, but then we don’t need a lot of other photobooks either. And Hashimoto Katsuhiko has a good eye. What’s shown here is for the most part a crumbling, rusty, even grimy provincial Japan, but there’s always detail for pleasurable examination.

There are 52 B/W photographs, printed rather cheaply. (To my completely inexpert eye, the printed photos look like an educational demo of the results of the first stage of duotone printing.) I’m no fan of matching printing process to content and think the book would be more successful in tritone (of course economically impossible), but the lack of reproduction finesse does seem to add its own minor fascination.

In the back a list understandable even for Japanese and English monoglots says roughly where and when each photo was taken. And Hashimoto provides an afterword in the two languages. As for himself, we learn that he was born in Tokyo in 1942 and that he’s in a photo group named “Myaku”. Here’s a completely unrelated award-winning photo by him. For six days in October he had a small show at Nikon Salon bis (see the sole B/W photo here); I wish I’d known of it at the time, because I would have gone to see it. And this is all I know.

This is a small, unpretentious, modestly priced, and satisfying book.

Here’s the announcement from Sōkyūsha.

Hatsuzawa Ari, Rinjin. 38-do-sen no kita (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten). 初沢亜利, 『隣人。38度線の北』(東京: 徳間書店). ISBN 978-4-19-863524-4. Some of the material on the copyright page is in English but elsewhere the book is only in Japanese. The title means “Neighbours: North of the 38th parallel”.

Hatsuzawa Ari, Rinjin. 38-do-sen no kita (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten). 初沢亜利, 『隣人。38度線の北』(東京: 徳間書店). ISBN 978-4-19-863524-4. Some of the material on the copyright page is in English but elsewhere the book is only in Japanese. The title means “Neighbours: North of the 38th parallel”.

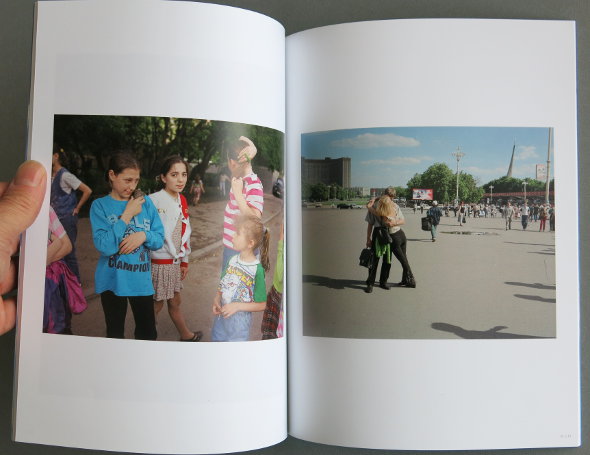

After his True feelings, a second photobook in one year by Hatsuzawa Ari, this time on North Korea, where he made four short trips from 2010. The book runs to 167 pages, of which pp. 5–78 are devoted to 平城 (Pyongyang) and pp. 79–153 to 新義州 (Sinŭiju), 咸興 (Hamhŭng), 元山 (Wŏnsan), 南浦 (Namp’o), 浮田 [?] and 金剛山 (Kŭmgangsan). Even in Japanese, there are no captions and there’s no other indication of whether the scene you’re looking at is (say) Hamhŭng or Wŏnsan.

Well, no matter. The neighbours north of the 38th parallel don’t always look so unlike the Japanese. They ride bikes, they frolic in the sea, they picnic, they wear Hello Kitty clothing — they tend to look rather normal as they go about their daily life. It’s a world away from the North Korea of Charlie Crane. (If the people stiffened or mugged for the camera, Hatsuzawa eliminated those photos.) This is no tourist memento but it’s sympathetic, and like True feelings it shows Hatsuzawa’s mastery of colour.

If Hatsuzawa’s book interests you, look also for Watanabe Hiroshi’s Ideology in paradise (パラダイス・イデオロギー): Watanabe’s cooler approach complements Hatsuzawa’s warmer one.

Ikazaki Shinobu, Inaya tol (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 伊ヶ崎忍, 『Inaya tol』(東京: 蒼穹舍). CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Ikazaki Shinobu, Inaya tol (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 伊ヶ崎忍, 『Inaya tol』(東京: 蒼穹舍). CiNii; here and here in Worldcat.

Ikazaki writes of Inaya Tol:

There is a very small and uncharted area on the Vishnumarti River, which flows behind the old royal place in Katmandu. This place is known as “Inaya [Tol]”. There are many Khasai buffalo slaughterhouses built tightly-packed in this area. Khasai people belong to the Newar, who were the earliest inhabitants [of] Nepal, and [are discriminated against].

He adds that the meat-eating Khasai are the lowest caste of the lowest class (or vice versa, or similar), but that their economic status has improved in recent years, so that members of (traditionally) higher castes/classes can now be seen employed by them.

There are no captions, in any language. There’s an afterword and a potted CV in Japanese and English, and that’s it.

The book alternates sections in B/W (printed well) and sections in colour (printed so-so). The former are more successful, but there are some fine photos in colour too.

There are dead animals (and bits thereof), live ones, and most disturbingly a live animal next to the head of a dead one, and a very small child wandering among the carnage. There’s a small amount of mild mugging by the workers, but not while they’re working: these aren’t psychopaths; they’re instead regular people doing a repellent job in a matter-of-fact way, which Ikazaki seems to view neutrally.

Here’s the announcement of the book at Sōkyūsha. It’s available from Japan Exposures.

Kimura Hajime, Kodama (Tokyo: Mado-sha). 木村肇, 『谺』(東京: 窓社). ISBN 978-4-89625-115-9. CiNii, Worldcat.

Kimura Hajime, Kodama (Tokyo: Mado-sha). 木村肇, 『谺』(東京: 窓社). ISBN 978-4-89625-115-9. CiNii, Worldcat.

I picked this off a shelf because I noticed “Kimura” and sleepily mistook the book for some new collection by Kimura Ihee (whose deservedly famous colour photography of Paris has outside Japan quite eclipsed his B/W work). Wrong: this book is by a different and much younger Kimura. But it’s no disappointment. (Indeed, new collections of work by Kimura Ihee tend to be either humdrum or very expensive.)

Kodama here means “echo”, with mountain/valley connotations. (Elsewhere it’s also a surname whose meaning, if any, is unrelated.) Kimura Hajime photographed on the snowy west coast of Japan, following hunters. Clothing aside, the scenes could be from the 1960s or even earlier — emphasized by the strong compositions and high contrast, as if this were newly discovered work by Kojima Ichirō.

A major annoyance: a significant number of the photos (including the excellent one reproduced on the front cover) are split across facing pages; and because the book is (unlike, say, Concresco) bound conventionally, the viewer’s brain then has to relate two separated chunks of a photo while ignoring a substantial median chunk. (Calling all photobook designers/publishers: Don’t do this.) But enough other photos can be enjoyed uninterruptedly. And there are captions in both Japanese and English for each.

Here’s Kimura’s page about his book.

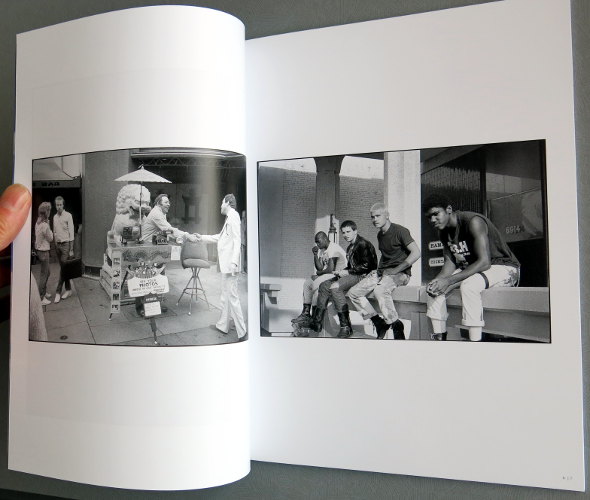

Ogawa Takayuki, New York is (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 小川隆之, 『New York is』(東京: Akio Nagasawa). Worldcat, CiNii.

Ogawa Takayuki, New York is (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 小川隆之, 『New York is』(東京: Akio Nagasawa). Worldcat, CiNii.

Ogawa Takayuki (1936–2008) was in New York for less than eleven months, from April 1968. Though he has long been known in Japan (p. 81 of The Observer’s Book of Japanese Photographers is devoted to him), and though CiNii reveals that he (or a namesake) provided the photographs for a 1980 book titled American antique dolls (アメリカ人形 アンティークドール), this seems to be his first real photobook. It’s quite a production, with texts by Nathan Lyons, Anne Wilkes Tucker and (very briefly) Robert Frank.

Look inside and you soon see that while it merits these texts it doesn’t need them. The book is compact (21×22 cm) and not cheap; but it’s also not exorbitantly priced and it has 120 or so excellently printed photos, which are in a sort of Ishimoto or Frank mode and (harder to pull off) are in the same league. There are no duds. This is good stuff indeed.

Here’s the book at its publisher’s website. There’s a helpful write-up on its sales page at Japan Exposures.

Ōtsuka Megumi, Tokyo (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 大塚めぐみ, 『Tokyo』(東京: 蒼穹舍).

Ōtsuka Megumi, Tokyo (Tokyo: Sokyusha). 大塚めぐみ, 『Tokyo』(東京: 蒼穹舍).

Visit half a dozen Tokyo photo exhibitions (something easily achieved in a single quarter of the city, in one afternoon), and chances are you’ll see at least one show of street photography. However feeble it might be, it will have more life in it than at least one of the non-street shows. And it could be very good. (One highlight this year: the first ever show by Komase Yutaka, still a student.) And then somehow the good stuff doesn’t get published. (I suppose it just doesn’t sell. People instead want little colour epiphanies, the diaristic, the whimsical, people posed to look blank, Sanai’s latest car, whatever.) Go to a photobookstore, and you’ll see that of the small selection of life-in-the-streets “street” material, much merely presents people just walking down the street toward the photographer, interacting not with the photographer or anyone or anything else, and instead just looking surly, glum or blank. The praise some of its long-term producers get sometimes seems to be for their sheer stamina; I wish them well but their work doesn’t tempt me.

But at last we have here a book of good new street stuff by somebody who’s (fairly) new. Tokyo presents 69 B/W photographs by Ōtsuka Megumi, taken from 2003 to 2012. The book design is minimal: I repeat that it’s by Ōtsuka Megumi as her name doesn’t appear anywhere on the cover or the title page (it’s only within the colophon). She was a student of Moriyama, but his influence is far less obvious than that of Friedlander. What you don’t get here are close-cropped photos of single people (surly, glum or blank) striding toward the camera. There’s always something going on, whether action or composition or both. Ōtsuka (also spelled “Ohtsuka”) has succeeded in putting out a book of Japanese B/W “street” photos that doesn’t make me long for Abe Jun’s Citizens or Kokubyaku nōto in its place. More than that, she even has photos of small kids doing the kind of mildly naughty thing (climbing up a traffic sign, two at a time) that conventional wisdom says (i) never occurs (the kids being glued to their Playstations or otherwise lobotomized) and (ii) would be unphotographable even if it did occur. (Plus she got some of her photos published in the current issue of the nervous Nippon Camera.)

Here’s the book at Sōkyūsha.

Suda Issei, Fushikaden (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 須田一政, 『風姿花伝』(東京: Akio Nagasawa).

Suda Issei, Fushikaden (Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa). 須田一政, 『風姿花伝』(東京: Akio Nagasawa).

In one of the good little essays masquerading as interview responses within the introductory material to the lavish 2011 “Only Photography” book on Suda Issei, Ferdinand Brüggemann rather reluctantly identifies the best section of Suda’s work. It’s the series Fūshi kaden, photographed in the seventies, serialized in Camera Mainichi from December 1975, collected in 1978 in a compact book within the popular series Sonorama shashin sensho, and in 2005 sampled within a utilitarian booklet for a JCII exhibition.

The title? Brüggemann explains, but this, this and (for you readers of Kurdish) this will give hints.

Suda was one of several photographers exploring the countryside of Japan — not a new idea (for example, the Edokko Kimura Ihee had spent a long time in Akita), but one that clearly excited Akiyama Ryōji, Naitō Masatoshi, Kitai, Takanashi, Tsuchida and others in this period as well as Suda. Suda concentrated on festivals, shrines and the like, photographing directly, clearly, and yet somehow elliptically. Hard for a lazy person such as myself to express well, so instead I’ll cop out and point you to a generous sample; and to views of the book itself. There’s variety, as you’ll soon see; but there’s no filler.

Suda not only got a volume within Sonorama shashin sensho, he also got one within the far more selective series Nihon no Shashinka, so he’s been known and respected in Japan for some time. (If he’s only recently become known in the anglosphere, it’s not for lack of advocacy. I suspect that the Euro-American obsession with Provoke is to blame.) But he hasn’t been trendy in Japan until recent years, as the price of the original Fūshi kaden book has joined those of the Sonorama shashin sensho volumes by Araki, Fukase and Moriyama; presumably bought up by people who plan to make a profit selling them to the kind of dimwit who also pays huge sums for books confidently advertised as “flawless” by a seller who admits to not having opened them to look for any flaws. (Pardon the rantlet.) The Sonorama shashin sensho books were good value thirty years ago, but the reproductions are small and poor by today’s standards. That and the high price of the Suda volume make a new edition particularly welcome.

But a new edition this isn’t. Not only does it add photos, it radically rearranges what it inherits from the older book (whose texts, in both Japanese and English, it also drops). For example, what was the first photo in the book is now the last. So think of it as a new and greatly improved selection from the same series.

The reproductions are bigger than they were in 1978, but not as big as in the “Only Photography” book, from which the printing quality differs too: the photos are glossier here and probably for this reason the blacks are slightly blacker. I hesitate to say they’re better, but even if (unlike me) you already have the “Only Photography” book they will not disappoint.

The book’s exterior is surely intended to help justify the book’s horribly high price and to impress; for me, the impression is funereal. No matter: the photographs are fascinating and the reproductions are fine; that’s enough.

There’s a short afterword by Suda, and captions (placename and year), all in both Japanese and English. There’s no explanation of what it is that you’re looking at, merely of when and where it transpired. The photos are enjoyable without this, but I’d be interested to read about them all the same. (In Once a year, itself long overdue for republication, Homer Sykes gave us photos and text.)

Here’s the book at its publisher. It is also available from Japan Exposures.

Suda publishing has recently been on an (overdue) roll. During the last few weeks there have been one and a half other new books by him: Rubber (colour, and very different from Fūshi kaden); and as an appendix to Fūshi kaden, 1975 Miuramisaki. The latter presents a grand total of six (6) photos, all of that one famous snake. Reproduction is superb; price is high. I was sorely tempted, but I already have too many photobooks (each with more than six photos) and so my ten-thousand-yen notes stayed in my pocket.

Tatsumi Naoya, Japan (Warabi, Saitama: Tatsumi Naoya). 辰巳直也, 『日本』(埼玉県蕨市: 辰巳直也). CiNii. The English title appears in the colophon.

Tatsumi Naoya, Japan (Warabi, Saitama: Tatsumi Naoya). 辰巳直也, 『日本』(埼玉県蕨市: 辰巳直也). CiNii. The English title appears in the colophon.

I’ve already seen more than enough photos of the backs (and perhaps the fronts too) of near-naked tattooed men, so the cover of this book wouldn’t have appealed; which is perhaps why it was months before I noticed it within Sōkyūsha’s excellent bookshop. For a self-published Japanese photobook, it was remarkably large and had a refreshingly bold title, so I ignored the tattooed male and picked it up.

The book’s about 30×21 cm; it’s unpaginated but about 18 mm thick. It consists of three parts: “Nishinari 1995–2001”, “Okinawa 2003” and “Shinjuku, 2007–2011”. Nishinari is an impoverished central borough (“ward”) of Osaka, and in this part Tatsumi Naoya presents street portraits of people who I suppose are occasional day labourers or are destitute. Not all the portraits are complete successes but enough are. The Okinawa section presents a good variety of Okinawa, in blazing colour: late Tōmatsu (more) perhaps here meets Uchihara’s Son of a bit (less). The Shinjuku section has (not quite so blazing) colour street photos of the entertainment area, concentrating on the young denizens with their chemically enhanced coiffure and painful shoes; a small percentage of duds here but the great majority have this or that kind of interest. All in all Tatsumi delivers not just volume but content and satisfaction.

Samples of the photos are here on Tatsumi’s site. Here’s the book at Sōkyūsha. It’s also available in various other [physical] bookshops in Japan (listed on Tatsumi’s site); via the internet from Flotsam Books, which takes PayPal but says nothing about sending anything outside Japan.

Want more, better-informed lists? A pile of them are conveniently linked from this Phot(o)lia post. Among them, I only notice one that’s (mostly) devoted to Japanese books: Mark Pearson’s, within (and about two thirds the way down) the BJP listorama. (Intersection of his list and mine: zero books. Indeed, I hadn’t even heard of four of his ten choices, so you now have some idea of the depth of my ignorance.)

PS (31 December): John Sypal has published, not his top ten, not his top three, but his top three of my top ten. I shan’t spoil the fun by divulging what they are; instead, see for yourself. As well as comment, he did what I couldn’t be bothered to do: take and provide photos of his choices (or anyway, of two of them).

PPS (31 January): And another list of favourite Japanese photobooks of 2012.

twenty-plus reasons why I can’t give you a “top photobooks of 2012” list

Posted: 08/12/2012 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists Leave a commentYes it’s “let’s congratulate ourselves on our acquisitions” season. But perhaps I shouldn’t make my own list. There are probably enough already, and every additional list might bring more grief to Marc Feustel. Plus I haven’t seen anywhere near enough of the books I already know that I want to see. (This year, I haven’t even once ventured into any bookshop outside Japan.) So here’s my pretty useless these look interesting but NB I haven’t actually examined any of them list for the year.

Feel free to click on any link. Rest assured that none goes to Amazon, the Book Depository (i.e. Amazon), Abebooks (i.e. Amazon), Shelfari (i.e. Amazon), or Junglee (i.e. Amazon). (Because no I’m not, and don’t want to be, an “affiliate” of Amazon or any other corporation.) Although some of the links do go to publishers that may have become divisions of Amazon while I wasn’t looking.

- Anita Back, Die Auserwählten – ein Sommer im Ferienlager von Orlionok = The select few: A summer in the holiday camp of Orlyonok (Braus)

- Hilton Ariel Ruiz and Beatriz Ruiz, eds, The forty-deuce: The Times Square photographs of Bill Butterworth, 1983–1984 (Powerhouse)

- Mark Haworth-Booth, Brandt nudes (Thames & Hudson)

- Asger Carlsen, Hester (Mörel)

- Michal Chelbin, Sailboats and swans (Twin Palms)

- Carl De Keyzer, Moments before the flood (Lannoo)

- Andrea Diefenbach, Land ohne Eltern (Kehrer)

- Harold Feinstein: A retrospective (Nazraeli)

- Tony Fouhse, Live through this (Straylight)

- Annett Gröschner and Arwed Messmer, Berlin, Fruchtstraße am 27. März 1952 = Berlin, Fruchtstrasse on March 27, 1952 (Hatje Cantz)

- Zisis Kardianos, A sense of place (Zisis Kardianos)

- Robert Knoth and Antoinette de Jong, Poppy: Trails of Afghan heroin (Hatje Cantz)

- Nicola Lo Calzo, Inside Niger (Kehrer)

- Michał Łuczak, Brutal (Michał Łuczak)

- Peter Martens, American testimony (Post)

- Davide Monteleone, Red thistle (Dewi Lewis)

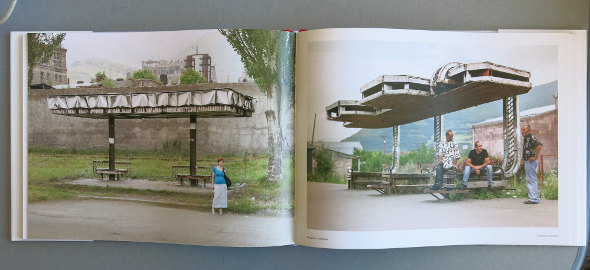

- Gyler Mydyti and Elian Stefa, Concrete mushrooms: Reusing Albania’s 750,000 abandoned bunkers = Ripërdorimi i 750,000 bunkerëve Shqiptar (DPR-Barcelona)

- Enrico Natali, New York subway, 1960 (Nazraeli)

- Cedric Nunn, Call and response (Hatje Cantz)

- Ostkreuz, Über Grenzen = On borders (Hatje Cantz)

- Inta Ruka, People I know (Max Strom)

- Gregor Sailer, Closed cities (Kehrer)

- Sputnik, Miejsce odległe = Distant place (Copernicus Science Centre)

- Hans van der Meer, The Netherlands: Off the shelf (Paradox/Ydoc)

- Tomas van Houtryve, Behind the curtains (Intervalles)

- Dirk-Jan Visser and Arthur Huizinga, Offside: Football in exile (Paradox/Ydoc)

- Malte Wandel, Einheit, Arbeit, Wachsamkeit. Die DDR in Mosambik (Kehrer)

Copies of two of the above are already on their way to me (from Canada and Poland). And I hope to see more of the others in the new year. So far as I can judge from little JPEGs, they’re all quite a bit more rewarding than some of last year’s top of the critical pops and than over 90% — but not all! — of the photobooks and -zines coming out of Japan.

top three Japanese photobooks of 2011

Posted: 30/12/2011 Filed under: Books | Tags: "best of" lists, Araki Nobuyoshi, Arimoto Shinya, black and white photobooks, Kikai Hiroh, photobooks from Japan Leave a commentThe top ten photobooks of 2011 — everybody else is listing them, so why not me? Answer: laziness! And so instead, my top three Japanese photobooks of the year: Read the rest of this entry »