Nakada Kenzō photographs down a tunnel

Posted: 29/07/2012 Filed under: Books, Shows | Tags: BeeBooks, black and white photobooks, JCII, Nakada Kenzō, photobooks from Japan Leave a commentIt’s been 24 years since the opening of the Seikan tunnel, linking Honshū and Hokkaidō (Japan’s two biggest islands). The tunnel’s 54 km long, making it the longest rail tunnel anywhere and over twice the length of the longest road tunnel. Planning and surveying took decades, construction started in 1971, and the tunnel opened in 1988. This Aomori government page makes the staggering claim that over time the number of workers totalled 13.8 million.

A search engine will find photographs of the construction of the tunnel. Here’s Jiji’s selection: strong on ceremony but weak on anything else. (The website of the tunnel museum offers stuffed dolls but not a single photo of construction.)

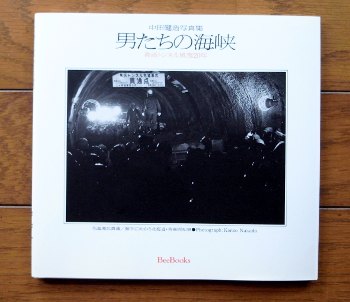

Look up 青函 (i.e. Seikan) in the OPAC of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, and there are three hits. One’s for a 1988 book about the ferry (now history). The other two are for a book about the tunnel: 男たちの海峡 青函トンネル風雪20年 中田健造写真集 Otoko-tachi no kaikyō: Seikan tonneru fūsetsu 20-nen: Nakada Kenzō shashinshū. (If you’re in the library, the call numbers are P810/N31-2/1 and P810/N31-2/1a.) The title means something like: “Strait of men: 20 years of Seikan tunnel hardships: A photobook by Nakada Kenzō” (“strait” as in Hormuz, not dire). This 1988 book is a very early entry in the BeeBooks series: according to its spine, no. 21; according to the publisher’s list, no. 23. It’s tiny: 17×18.5 cm and about fifty pages. Printing quality is 1980s (some later BeeBooks would have superb printing), and some pages have as many as twelve photos (all B/W). You get the sense that the book doesn’t do the photographs justice, but sometimes the reproductions are so short of detail that you can’t be quite sure.

Look up 青函 (i.e. Seikan) in the OPAC of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, and there are three hits. One’s for a 1988 book about the ferry (now history). The other two are for a book about the tunnel: 男たちの海峡 青函トンネル風雪20年 中田健造写真集 Otoko-tachi no kaikyō: Seikan tonneru fūsetsu 20-nen: Nakada Kenzō shashinshū. (If you’re in the library, the call numbers are P810/N31-2/1 and P810/N31-2/1a.) The title means something like: “Strait of men: 20 years of Seikan tunnel hardships: A photobook by Nakada Kenzō” (“strait” as in Hormuz, not dire). This 1988 book is a very early entry in the BeeBooks series: according to its spine, no. 21; according to the publisher’s list, no. 23. It’s tiny: 17×18.5 cm and about fifty pages. Printing quality is 1980s (some later BeeBooks would have superb printing), and some pages have as many as twelve photos (all B/W). You get the sense that the book doesn’t do the photographs justice, but sometimes the reproductions are so short of detail that you can’t be quite sure.

It’s not that there are other books and the museum’s library is simply weak in the genre of tunnel-construction photography. As far as I know, Nakada was the only photographer to have spent much time in the tunnel before its completion, his is the only sizeable collection of photos of the construction process, and this is the only photobook that exists.

Nakada very generously gave me a copy of this rare book when I visited his current exhibition. Today’s the last day of this show at JCII of a different selection of the same title (男たちの海峡 青函トンネル風雪20年 Otoko-tachi no kaikyō: Seikan tonneru fūsetsu 20-nen). The wall-space isn’t wasted, but the prints are big enough (and excellently printed). And there’s a 32-page booklet of the kind that normally accompanies a JCII show, a booklet that like the earlier book is rather too full, with as many as six photos per page. Again, some do little more than jog the memory of what you’ve seen. Gems among them: top left on p.11, top left on p.16, bottom of p.22.

Not all the photos are of work. There are perhaps one or two too many of work-related celebrations and ceremonies. But there are also good photos of family life: p.27 of the JCII booklet has two in particular: one of a couple of boys nonchalantly dragging their bags along the road and another of a mother and two young children that might be one of the high points of an early book of Araki’s.

But mostly they are of work. When Douglas Stockdale recently asked about photobooks about work, I had trouble coming up with Japanese examples. Two generations ago Japanese photographers whether international (Hamaya Hiroshi) or local (Shimizu Bukō) photographed work, but there’s little sign of this among the contemporary Japanese photobooks at London. Predictably, a visit to NADiff two days ago brought nothing related; instead, I was mostly treated to photographers artists working in lens-based media tastefully exploring and exhibiting their sensibilities (which tended to resemble each other). All very worthy, but my own tastes instead run to Yamamoto Sakubei.

Paging photobook publishers: If there were a well-edited, sensibly-sized collection of Nakada’s photos in duotone, I’d buy a couple of copies.

All the images above are copyright © Nakada Kenzō.

peaks from the 1920s–1940s, at JCII Photo Salon

Posted: 09/12/2011 Filed under: Shows | Tags: Fukuhara Rosō, Fukuhara Shinzō, Japan, JCII, Nakayama Iwata, photo exhibitions, Yasui Nakaji Leave a comment Until 25 December, JCII Photo Salon has a stunning exhibition of work by four photographers: Nakayama Iwata (中山岩太, 1895–1949), Yasui Nakaji (安井仲治, 1903–42), and the brothers Fukuhara Shinzō (福原信三, 1883–1948) and Fukuhara Rosō (福原路草, 1892–1946).

Until 25 December, JCII Photo Salon has a stunning exhibition of work by four photographers: Nakayama Iwata (中山岩太, 1895–1949), Yasui Nakaji (安井仲治, 1903–42), and the brothers Fukuhara Shinzō (福原信三, 1883–1948) and Fukuhara Rosō (福原路草, 1892–1946).

For those poor souls who think that it wasn’t until Provoke that Japanese photography emerged from its Dark Age, the names won’t mean much. (Tip: There was no Dark Age. See The History of Japanese Photography.) But those who know better will recognize all four names and also plenty of their work. At first glance Fukuhara Shinzō’s earliest work may now seem little more than decorative, but in its day it was a refreshing change from the overtly painterly styles (with bromoil, etc) that prevailed. And he moved on from there, while his brother Rosō went still further. (Shinzō also found time to run Shiseidō, and indeed to do so very well.) Nakayama and Yasui each attempted a far wider range, and both succeeded: photograms, portraits, surrealistic montages, and (for Yasui) reportage too. And it’s all fine, in its way.

In the 1970s, the Pentax Spotmatic (with a little gold quality-assurance sticker from JCII) was selling well, and its maker Asahi Optical was able to buy fine prints (as well as cameras of historical value) for its Pentax Gallery. When this closed in 2009, JCII acquired much (or all?) of its content. And at the core of this exhibition are works that were previously at the Pentax Gallery, which was clearly run by people who knew what they were after and had the funding to get it.

But that’s not all. As well as vintage prints from Pentax, the exhibition also has more recent ones. And under glass cases near some of the prints are magazines of the time (not only camera/photography magazines, but also general magazines), showing how the photographs first appeared to the public — often very differently from the current prints.

The exhibition occupies both of JCII’s exhibition spaces, so in terms of quantity it’s comparable with a small exhibition in a museum. The explanations are in Japanese only, which is a pity — but at least the photographers’ names are also given in roman lettering. And unlike many bigger shows, there’s no filler. Entrance is free, and if you go during a weekday you may have a whole room to yourself. Highly recommended.

JCII Photo Salon is a very short walk from exit 4 of Hanzōmon station (Hanzōmon line), in very central Tokyo. (Here’s a map.) It’s normally open 10:00 to 17:00, Tuesday to Sunday; if a national holiday falls on a Monday, it’s open on this Monday but closed the following day.

Here’s the exhibition notice (in Japanese).

(The articles in [English-language] Wikipedia on Yasui Nakaji, Fukuhara Shinzō and Fukuhara Rosō are all terrible but each has some material that could be useful.)

Watabe Yūkichi

Posted: 02/12/2011 Filed under: Books | Tags: Alaska, black and white photobooks, Japan, JCII, Morocco, photobooks from France, photobooks from Japan, Sonorama Shashin Sensho, Watabe Yūkichi 2 Comments

When the book A Criminal Investigation, by Watabe Yūkichi (渡部雄吉, 1924–1993), came out, I knew that if it was as good as Watabe’s Morocco (seemingly unknown outside Japan), it would be good indeed — but it cost more than I was in any rush to pay. Eventually I got hold of a copy.

A Criminal Investigation

Here you have A Criminal Investigation, a 2011 book whose elegance has entranced a number of reviewers.

Let’s not dwell on the elegance. After a couple of photographs to set the scene, short texts in French and English (but oddly, not Japanese) explain that the discovery of certain body extremities raised the question of whom they’d been attached to and led to the discovery of the disfigured and burned remainder, identified as “Sato Takashi” (i.e. Satō Takashi). Though the body had been found in Ibaraki, Satō had come from Tokyo — yes, Tōkyō, but I’m not claiming total consistency here — and so the Tokyo Metropolitan Police were called in.

One particular policeman was involved, it would seem: the photographs follow him. We’re not told his name. Actually we’re not told anything else until about halfway through the book, when we’re told that the police were looking for, and had an arrest warrant for, a man (Nishida) who’d stayed at the same “hotel” (I’d guess flophouse) as the deceased.

Toward the end of the book we’re told that this was a dead end and that the investigators were stuck. There are a few more photographs. After these, we learn what was discovered a few months later within a much larger investigation. The perp was “Onishi Katsumi” (Ōnishi Katsumi 大西克己), who’d murdered three others too. (For more on Ōnishi’s unusually lurid story, see this or this — both in Japanese, but perhaps translations by Google etc will be comprehensible.)

Luckily we’re not shown any part of the deceased. What we are shown is the puzzled detective and his younger sidekick looking around, talking to people, and looking baffled. Necktie, overcoat, cap — Japan looked better before polyester and brand names (even if, with all those cigarettes, it smelled worse). But although the content is handsome (like the packaging, of course), it’s pretty uneventful after the alluring blurb on the back cover.

You’ll find other reviews at or by 5B4, the National Media Museum, CroCnique, Le Monde, and Atsushisaito.

Postwar Japan

A very grotty copy of the booklet made for an earlier exhibition at JCII Photo Salon of Watabe’s work. (Mine was tucked into the tired copy I bought of Watabe’s Morocco.) Various series are sampled here: both “A criminal investigation” and the capes of Japan, but also life on canal boats, Hokkaidō, and more.

A very grotty copy of the booklet made for an earlier exhibition at JCII Photo Salon of Watabe’s work. (Mine was tucked into the tired copy I bought of Watabe’s Morocco.) Various series are sampled here: both “A criminal investigation” and the capes of Japan, but also life on canal boats, Hokkaidō, and more.

First, a couple of spreads from “A criminal investigation” (1957):

From the series “A typhoon has landed” (Taifū ga kita), on Yoron-jima/Yorontō (1957):

From the series “Men of the mountains” (Yama no otoko-tachi), mining for sulphur on Meakan-dake (1959):

Here’s JCII’s page advertising the booklet. Even though it’s almost twenty years old, it’s still in print.

Indeed, if this page is to be believed, among all the booklets JCII has published since 1991, only one is out of print. As for the the remaining titles (more than two hundred of them), most (all?) are uncontaminated by roman script (aside from “JCII Photo Salon”) and are therefore sure to improve your Japanese, to bemuse you, and to impress your friends. Putting aside membership of the friends of the “Salon”, there are two obvious purchasing options:

- Go to JCII and buy them. JCII is in central Tokyo.

- Phone JCII and ask. JCII speaks Japanese and has a Japanese bank account.

(And I’ll try to come up with less obvious options if there’s any interest.)

To the sea

Here’s the catalogue of the show I wrote up before. Again, it shows a variety of the capes of Japan, and the photographs were taken close to half a century ago.

Here’s the catalogue of the show I wrote up before. Again, it shows a variety of the capes of Japan, and the photographs were taken close to half a century ago.

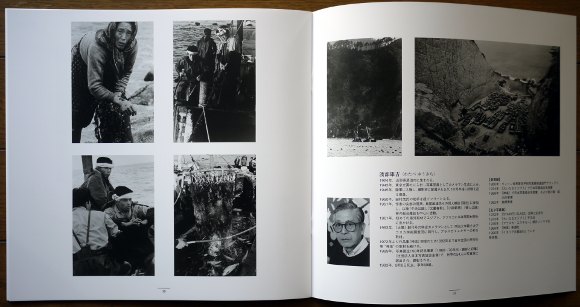

Below: Like all of these JCII booklets, it starts with a preface by Moriyama Mayumi, the head of the “Salon” and an amateur photographer (though better known to the general public as a government minister). On the right is a preface by Watabe’s second son.

Cape Shiretoko, on a peninsula jutting east from Hokkaidō and even colder than you might imagine:

Cape Inubō (“howling dog cape”), in Chiba:

Cape Seki, on Sado:

Cape Seki, in Miyako, Iwate; and a little bio of Watabe:

Here’s JCII’s page advertising the booklet.

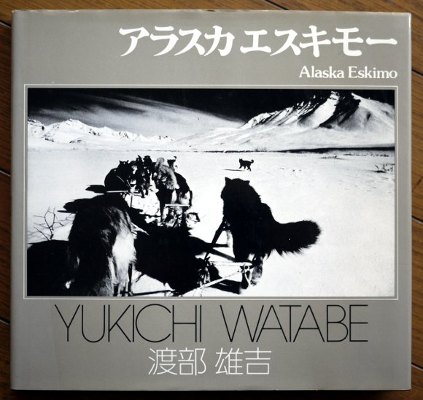

Alaska Eskimo

Entire books by Watabe are devoted to each of Venice, Suzhou, Egypt, Andalusia, France and more. Some will be of little interest to photobook fans; they were instead simply intended for people who, back before Wikimedia Commons, Flickr and the rest, wanted to see photographs of and read about this or that place. (Nagano Shigeichi and Ueda Shōji are among the many fine photographers who did similar work.)

Entire books by Watabe are devoted to each of Venice, Suzhou, Egypt, Andalusia, France and more. Some will be of little interest to photobook fans; they were instead simply intended for people who, back before Wikimedia Commons, Flickr and the rest, wanted to see photographs of and read about this or that place. (Nagano Shigeichi and Ueda Shōji are among the many fine photographers who did similar work.)

By contrast, Alaska Eskimo was published within “Sonorama Shashin Sensho” (ソノラマ写真選書), one of the very earliest (1977–80) of Japanese series of books produced for people interested in photography itself and not only the scenes, people or objects that the photography showed. Each of the 27 volumes is worth a look. Perhaps half a dozen among them now cost a lot as the particular photographer (Moriyama, etc) has developed a cult, but the remainder can be picked up for less than their original price (adjusting for inflation) if you avoid a handful of shops that cater to rich dimwits. Each has both an afterword and a potted bio in English. Reminders that the series is a generation old: (i) the printing quality; (ii) every photographer is male; (iii) every plate (I think) in every volume is in black and white.

The photographs in this book were taken in 1962, when Watabe, working for the publisher Heibonsha, accompanied a research group from Meiji University led by the ethnologist Oka Masao (岡正雄). (For a quick background to such expeditions of around this time, see the very readable abstract to this paper.) Some of the photographs would appear in the first issue of Heibonsha’s magazine Taiyō.

Below, please excuse my thumb.

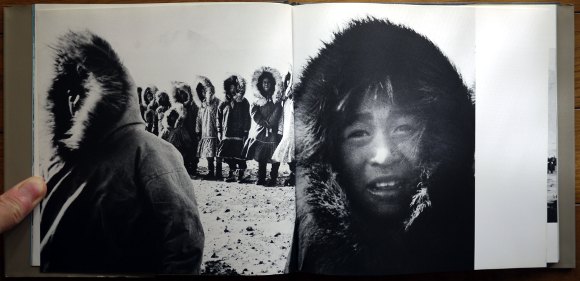

From part 1, “Inland Eskimo” (Anaktuvuk Pass):

From part 2, “Coast Eskimo” (Point Barrow):

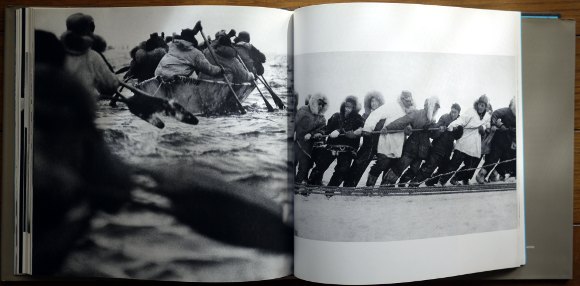

From part 3, “Whaling feast” (Point Hope):

Almost at the end of the book is a double-page spread of four photographs of people silhouetted against the sky (thanks to a trampoline). It’s an extraordinary close. (I’m sure I’ve seen something similar in a much later book, but I can’t think which. Ideas?)

atsushisaito presents more photos of the book here.

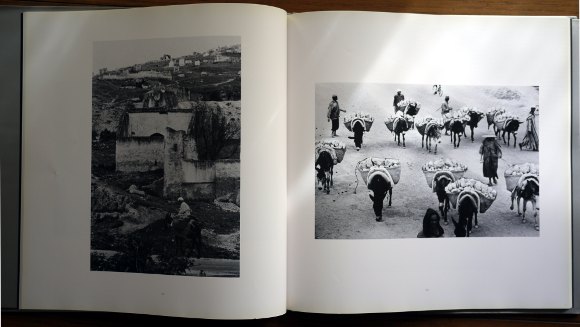

Morocco

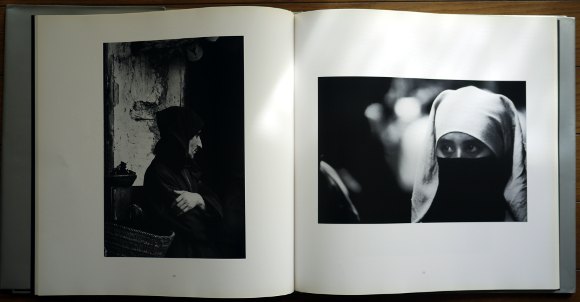

Morocco, with a Japanese subtitle meaning “the road(s) to (the) labyrinth(s)”.

Morocco, with a Japanese subtitle meaning “the road(s) to (the) labyrinth(s)”.

The unopened book looks like those in a series from Iwanami Shoten, each by a middle-aged or older photographer who very competently presents the architectural or other treasures of this or that part of the world. In other words, worthy uses of a library budget but somewhat unexciting.

Open the book, though, and you have a happy surprise. Yes, there are picturesque buildings. But there are street scenes, street portraits (both environmental and tightly framed), architectural details, the Atlas, the desert: the lot. It’s hardly surprising when we read that Watabe visited Morocco seven times. He worked as hard as any photographer commissioned to make a tourist trophy, but with far more stimulating results.

There are 92 plates and depending on your particular taste you might think of cutting this or that group of five or so among these. And for all I know the book may exoticize the Morocco of twenty years ago. (I wouldn’t know: I haven’t been there since a long time before that.) The printing could be slightly warmer, or of course in tritone. (And I wish my copy weren’t so speckled with mildew: I worry that it could infect its neighbours.) But it’s good:

The Japanese branch (“.co.jp”) of a certain US book monopolist currently (2 Dec ’11) offers six used copies of this book, each for around 15% the price of a new copy of A Criminal Investigation. The book didn’t win any design award, so far as I know, and it certainly wouldn’t do so now; but it’s worth your money.

Here’s a page about an exhibition by Canon of its holdings of photographs by Watabe of Morocco.

Copyright of the images shown above of course belongs to the estate of Watabe Yūkichi or the respective publisher, not to me.

January 2012 PS: There’s perceptive comment and also fresh information in Marc Feustel’s “Books of the Year: Yukichi Watabe’s A Criminal Investigation” (20 December 2011).

Watabe Yūkichi and the sea

Posted: 20/11/2011 Filed under: Shows | Tags: Japan, JCII, photo exhibitions, Watabe Yūkichi Leave a commentSome months ago there was a flurry of interest in French- and English-language websites over the photographer Watabe Yūkichi 渡部雄吉 (1924–1993), or anyway in the 2011 book of his work A Criminal Investigation. He was described as obscure, which surprised me until I realized how little there was on him in English on the web. So I started to put together a little piece about two of his other books. While doing this I looked for some recent material on him in Japanese — and two days ago discovered that there was an exhibition of his work going on here in Tokyo. And so of course I went along the next day.

The exhibition is Umi e no michi (海への道) — which means “(the) road(s) to (the) sea(s)” — and it’s showing at the JCII Photo Salon until 27 November. Here’s the JCII building:

The JCII is a camera quality association. Worthy though it is, neither it nor its building is remotely fashionable. Fine with me. Anyway, it’s a minute’s walk from exit no. 4 of Hanzōmon station on the Hanzōmon line — which puts it in very central Tokyo, right next to the curiously opulent British embassy.

The gallery is not so big, not so small. Exhibitions here often maximize quantity as well as quality. Again, fine with me. If I ever want elegant expanses of blank wall between photographs I can see them in DLK Collection; more often I want to see photographs. This exhibition doesn’t disappoint:

Most of the “Umi e no michi” exhibition consists of the series “Umi e no michi”, which first appeared in Asahi Camera month by month from January until July of 1963. Both on the walls and in the printed catalogue (¥800), the photographs are considerately identified by month and place — but, not quite so considerately, only in Japanese. So here you go; the locations (most with a link to the relevant article, whether good or bad, in Wikipedia):

- January: Cape Shiretoko (Shiretoko-misaki, 知床岬)

- February: Cape Sada (Sada-misaki, 佐田岬)

- March: Cape Tappi (Tappi-saki or Tappi-zaki, 竜飛崎; at the far north of the Tsugaru Peninsula)

- April: Cape Inubō (Inubō-saki, 犬吠埼)

- May: Cape Tsunegami (Tsunegami-misaki, 常神岬; here at Itouchmap)

- June: Cape Seki (Seki-zaki, 関岬; or Sado Seki-zaki, 佐渡関岬; here at Google Map)

- July: Cape Todo (Todo-ga-saki, written in a dizzying variety of ways including 魹ガ岬 and とどヶ崎; within Miyako)

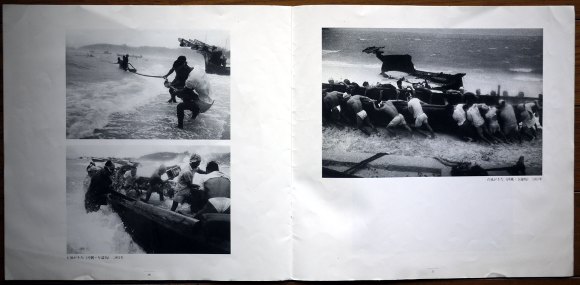

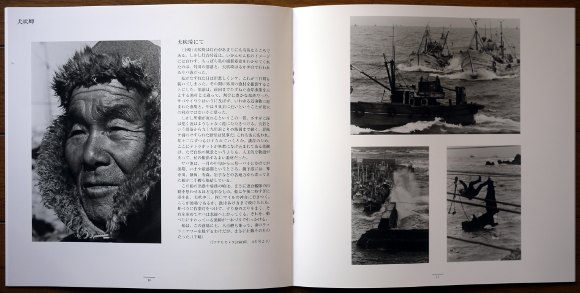

In short, Watabe made a journey to a stunning collection of some of Japan’s most remote and wildest places, and no doubt got drenched in sea-water and froze and felt sick — it’s sometimes clear that he’s on a small boat — as he observed fishermen and fisherwives and other fisherpeople at work, without goretex or velcro or many of other conveniences we take for granted. There no doubt was some tourism in Sado (even now not quite, as Wikipedia bizarrely puts it, “a city located on Sado Island”) — Kondō Tomio showed tourism well before Watabe reached Cape Seki — but there’s no sign of it here. Just people battling the elements as they deal with fish.

A description — grizzled faces, backs bent under the weight of baskets, etc — might make it all sound terribly earnest and passé, a throwback to the times of Domon Ken perhaps crossed with the 小説のふるさと of Hayashi Tadahiko. But so? Hayashi’s work is virtually free of the sentimentality that his title suggests, and this kind of Domon is fine with me (whereas I’ll forgo his photos of Buddhist statuary). If Watabe’s work had rather more grain, contrast or burning in, people would compare it that by his coeval Kojima Ichirō and it might get the “Hysteric” treatment.

Decades later, Ishikawa Naoki would make a comparable effort with Archipelago with a very different result; it’s OK, I suppose, but to me somehow tepid. Watabe can do people as well as places, and his work is far more exciting.

And as a bonus, the gallery adds works from other series by Watabe. Among these is the “Criminal Investigation” series. At the right in my photo above are three prints from the “Yama no otoko-tachi” series, of miners in Hokkaidō.

Miscellaneous notes for anyone who sees the show and might be . . . “Japanese-challenged”: Yes, that’s a selection of Watabe’s books in the perspex case. It’s far from an exhaustive collection: it strangely omits his big and award-winning book Kagura (which at least is mentioned in his potted bio) and of course the new Parisian production A Criminal Investigation (which isn’t mentioned anywhere). If two of his cameras, also displayed there, look improbably pristine, this is because they’re not his but instead examples of Leica (with 25mm Canon lens and finder) and Pentax from JCII’s large collection, a generous selection of which is on display in the basement of the same or next building (different entrance, and admission costs ¥300).

Here’s the exhibition notice (with a stylized map at the foot). And here’s a page about the exhibition catalogue (and here’s a description of it in English). So far it’s all in Japanese, but here’s a stylized map in English. And this is Google’s map for it.

Remember, this exhibition closes soon: 27 November. While it’s still showing, it closes every day at the old-fashioned and inconveniently early time of 5 p.m. But it’s free (and far more rewarding than several exhibitions elsewhere that cost me money).