Obara Kazuma is the man

Posted: 17/09/2012 | Author: microcord | Filed under: Books | Tags: Fukushima Kikujirō, Obara Kazuma, photobooks from Japan, photobooks from Switzerland, Sanriku earthquake/tsunami/radiation |3 CommentsThe brief (with numbers added): to nominate up to five photographers

- who have demonstrated an openness to use new ideas in photography,

- who have taken chances with their photography and have shown an unwillingness to play it safe.

On top of these (and implied numbers 3 recently and 4 who you happen to think of), I’ll add one more:

5. And whose work is good.

Er . . . Asger Carlsen?

But has he really taken chances? He’s good at what he does (and if Hester is ever published, I’ll buy a copy). But once he’s got the consent forms from the models, manipulating photos of nude ladies and marketing the results seem pretty safe. It’s not as if he were living in Iran.

Others . . . with Bee, Rose-Lynn Fisher uses an idea in photography that’s stunningly new (to me).

But then again (i) it’s three years old and (ii) for all I know scanning electron microscope photography is a well established technique/genre, if little promoted in the bookshops I frequent.

All too complex, so I’ll stick to Japan, where I happen to be. It’s a small nation facing plenty of real issues, very often eclipsed by junk food news (AKB48, the “Senkaku” islets, etc). Among the real issues are a large earthquake and tsunami (sixteen thousand deaths confirmed, three thousand more almost certain), continuing leaks of radioactive material, negligence leading to those leaks, evasiveness and dishonesty about the negligence and its results, pandemic fantasizing and nimbyism about major alternatives to nuclear power, huge consumption of electricity and other nations’ forests, stigmatism and discrimination.

Photographers of course have been under no obligation to pay attention to any of this, but you’d think that some would. And indeed there have been artistic responses. Jens Liebchen pointed his camera out of the window during a two-hour trip far from the area flattened by the tsunami (Tsukuba–Narita 2011/03/13). Ōmori Katsumi photographed cherry blossoms and (it seems to me) photoshopped in raindrops or halation (Everything happens for the first time). Kawauchi Rinko made some pretty thing with a black and a white bird (Light and Shadow). All no doubt well intended (the proceeds from at least one of these go to some unspecified charity), but all curiously insipid.

Luckily there’s been better work on the subject, even by the famous. Hatakeyama Naoya’s new book Kesengawa has good photography. (Unfortunately the book has a perverse design, in which many of its “portrait”-format pages are occupied half by a “landscape” photo, half by white space.) Shinoyama Kishin has put out a worthwhile book too (Atokata). And there have been good books by people who deserve to be better known: Hatsuzawa Ari’s True Feelings, Kōda Daichi (幸田大地)’s Bōkyaku (忘却), and more.

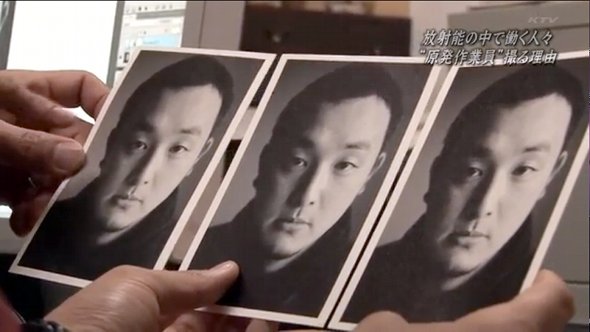

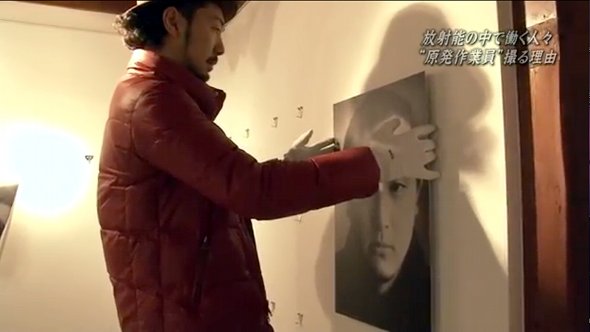

What haven’t yet had so much coverage (necessarily with text as well as photos) are the lives of those affected. I could name three or four worthwhile books that do present them, and among them one stands out. It’s from Switzerland: Reset: Beyond Fukushima, by Obara Kazuma (小原一真). The book isn’t conspicuous in Japanese bookstores (I only learned of it via the review at Conscientious), but it deserves to be in every library here. Obara illicitly entered a damaged reactor building, observed and photographed there, photographed and interviewed the people working there, and photographed more besides, for a substantial book.

Obara says of the photo above:

You can see the No. 2 reactor in the foreground on the left, and behind it, slightly obscured, the shell of the No. 3 reactor. I was shocked to see so many exposed pipes. They had never been shown on TV. On August 1, Tepco announced that radiation of 10,000 millisieverts per hour had been detected between reactors 1 and 2, not far from the sign, in red lettering, that reads “With one heart: never give up, Fukushima.” Spending just one and a half minutes there would take a plant worker above his maximum allowable dose of 250 millisieverts. And nothing was ever explained to them, even after the announcement. When I left the plant at the end of the day I underwent a radiation check that showed I had been exposed to 60 microsieverts in the space of six hours. I am a little concerned about the long-term effects that may have on my health, but I’m more worried about the young men who work there day in, day out.

This man says:

[. . .] it was tough going at the beginning, so tough, With people passing out one after the other at the plant, I thought it couldn’t just be the radiation’s influence. Thought I’d die of overwork or mental stress. Your head gets heavy and I would feel unbearable pain after only one and a half or two hours of work. I told myself I would die anyway, whether I continued working or not. That really was awful. I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to go on. On top of that I had a strong feeling that we were by no means following any emergency evacuation manual—something that still doesn’t exist to this day. Still, I’m not as pessimistic as the TV reports. [. . .] Everyone must be thinking that the people of Fukushima are worn out and exhausted, the city discouraged. They keep on encouraging us to hang in there, but we already are.

Reset: Beyond Fukushima has the sub-subtitle Will the Nuclear Catastrophe Bring Humanity to Its Senses? Will it? No it won’t: Enough people will be happy if lignite or any old crap is burned for electricity, as long as it’s not upwind. As for real reductions in power consumption: only if they’re painless. (The idea of not using air conditioning brings incredulous looks here.) So we know the answer, and to put the on the cover makes the book sound much more preachy than it is. Ignore the question and get hold of a copy (ISBN 3037782927).

- Obara has demonstrated an openness to use new ideas in photography. Photographically, not really. But journalistically, a daring idea, or anyway in Japan, with its incurious and docile mass media corporations (see Laurie Anne Freeman, Closing the Shop).

- Obara has taken chances with his photography and shown an unwillingness to play it safe. Japanese corporations have moved on a bit since Chisso had Eugene Smith beaten up, but yes. Those risks aside, yes, measurable via geiger counter.

For your reading and viewing pleasure:

- “Fukushima: the first man to photograph the Japan nuclear crisis”, Photography Monthly, 5 October 2011.

- Roku Goda, “Fukushima heroes featured in Kyoto exhibition”, Asahi Shinbun, 2 August 2012.

- Justin McCurry, “Fukushima cleanup recruits ‘nuclear gypsies’ from across Japan”, The Guardian, 13 July 2011. Not about Obara’s work but about the same issue.

- Obara Kazuma and Justin McCurry, “Inside the belly of the beast”, Number 1 Shimbun, Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan.

- video about Obara’s work, in Japanese and German

- video about a show in Paris of Obara’s work, in Japanese and French

- video of Obara at work, in Japanese only

- Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Committee, report

Anyone else of note? Japan’s “first female photojournalist”, Sasamoto Tsuneko (笹本恒子) has just had new books published. Here (video, Japanese only) she is. I only hope I’ll be that sharp when I’m 97.

The more youthful (91) Fukushima Kikujirō (福島菊次郎) continues to work: at 90 he was photographing Fukushima (the place) and was the subject of a new documentary film. Here’s its trailer — in Japanese only, but, thanks to Dan Abbe, with an English translation. The best-known work by Fukushima (a fairly common surname) is a long-term study of an atomic bomb survivor made during the 1950s, but time, age, cancer and a low income haven’t led him to acquiesce in the lies of Japan (the title of the film).

I haven’t seen the film yet but mrs microcord reports that it’s good. (She’s now reading the first of three volumes (of text) by Fukushima on utsurunakatta sengo, the unphotographed postwar era.) Here’s more recent material about Fukushima (the man):

- “From Hiroshima to Fukushima: Hidden Japan through the eyes of a legendary photographer, Kikujiro Fukushima”, Asahi Shinbun.

- Louis Templado, “Directing a documentary based on ‘lies’ captured by photojournalist”, Asahi Shinbun, 19 July 2012.

- Louis Templado, “Documentary depicts photographer Fukushima’s tumultuous life”, Asahi Shinbun, 22 March 2012.

- Louis Templado, “Fukushima an open-ended conclusion to photographer’s long career”, Asahi Shinbun, 8 March 2012.

- Mark Schilling, “Nippon no uso: Hodo shashinka Fukushima Kikujiro 90-sai (Japan Lies)”, Japan Times, 3 August 2012.

- Yuki Tanaka, “Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro: Confronting images of atomic bomb survivors”, The Asia-Pacific Journal vol 9, issue 43 no 4, 24 October 2011.

- video about him (a segment from a TV show, in Japanese only)

And so:

- Fukushima has demonstrated an openness to use new ideas in photography. Ah, here’s the problem. All I’ve seen from him this century are three photos quickly flashed at the viewer during the trailer for the documentary. Journalistically, it’s what ought to be routine: documenting what must be documented.

- Fukushima has taken chances with his photography and shown an unwillingness to play it safe.. Yes, he’s so frail that he’s taking a chance in merely showing up. Yes, the safe (and “sensible”) course would be to enter and stay within an old people’s home.

I can’t praise a photographer so highly when I haven’t seen the photos, and therefore microcord’s special summer 2012 accolade goes to Obara alone. But all power to Fukushima — I will see the film, and I hope to see his recent photos too.

I think I saw Obara’s photos when they were featured on The Guardian’s site, but it’s nice to see your fuller presentation here. That last video you posted of Obara is very enlightening, I can agree with his stance. I will make sure to swing by DELFONICS in Shibuya to take a look at the book.

[…] Colberg y Colin Pantall, en otros blogs como aCurator, reciprocity failure, La Pura Vida, fototazo, microcord, o en el blog de otro ilustre prescriptor como Harvey […]

[…] Peter Evans: Obara Kazuma […]